From The Portrait, 2nd Edition by Glen Rand and Tim Meyer

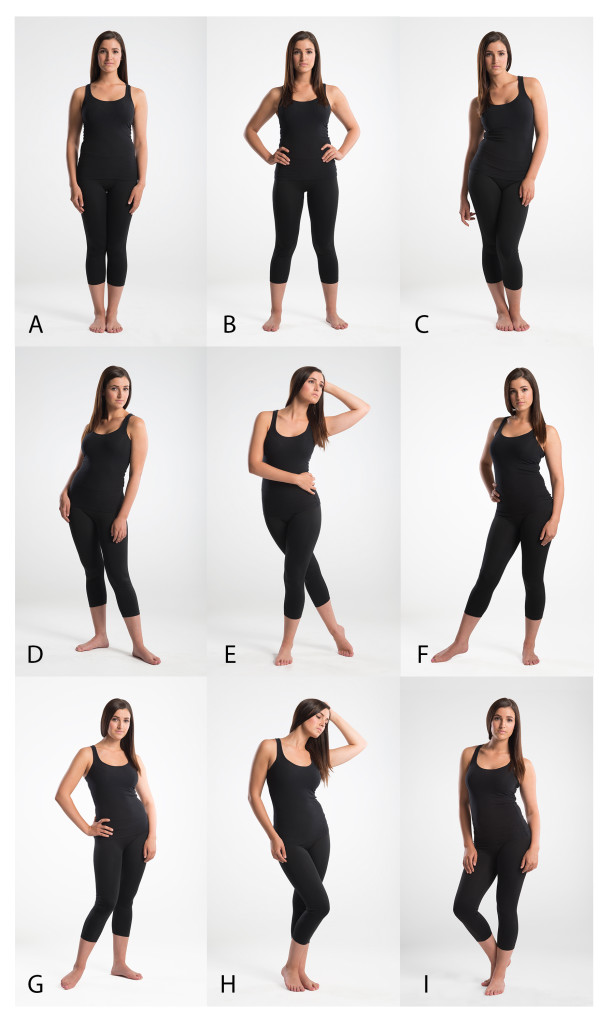

Posing requires directing the subject to change physical position to increase visual interest, flatter, imply emotion, or communicate intent to the viewer. This is done by rotating the subject, tilting the head, positioning the subject’s body, and employing clothing and accessories.

The first issue in approaching posing is the amount of the subject’s body that makes up the portrait. There is no specific advantage to one approach or another, as each gives a different look. Primarily, we speak of full length, three-quarter, bust, and closeup portraits. The most common pose is the bust that includes the total head without cropping and the upper part of the torso. A full-length pose need not be a standing portrait, but it will show the entire body. The least frequently used pose is the three-quarter view that includes the head and full torso but seldom shows the body below mid-thigh. Last is the closeup or full-face portrait that crops tightly on the face and does not show the shoulders.

Regardless of how much of the subject will be seen in the portrait, posing starts at the feet. Whether the subject is seated or standing, or the portrait is full-length or closeup, the placement of the feet creates the foundation for the portrait and determines the posture of the subject. The Greeks gave us the concept of contrapposto (ironically, an Italian phrase depicting a Greek concept), which refers to the placement of the subject’s weight on one foot, often the farthest foot from the photographer, and the relaxation of the front foot. This minor weight shift creates movement in the line of the spine, alters the axis of the hips and shoulders, and implies a sense of ease in the subject.

Other positions of the feet convey various other body concepts. With the double flatfooted stance, there tends to be static placement of the shoulders, hips, and spine. When used in “at attention” mode, it recalls military or historic statues. This foot structure restricts the motion of the hips and increases muscle tension to maintain balance. The muscular and skeletal tension progresses up the body to the neck and face. While tension is created throughout the portrait by rigid symmetrical feet positioning, when the feet are more relaxed, they can produce poor posture.

It is common for women to stand in the contrapposto fashion while exaggerating the curve of the spine to create the C or S curve. The amount of exaggeration is determined by the genre of portraiture. While men also take advantage of the contrapposto postion, the hip maintains an angular and therefore a more masculine feel. When the weight is placed on the front foot, even while sitting, the body’s weight moves toward the camera and creates a more aggressive statement.

This chart shows nine poses that are common for female full-body posing.

Just as the feet begin the pose, the legs transfer the posing energy to the hips. In turn, the hips set the angle for the torso, defining the spine angle and establishing the head tilt potential. Depending on the flexibility of the torso, the posing of the mid-body sets up how relaxed or tense the shoulders and neck appear.

With the exception of full-face and closeup portraits, the shoulders or their posing are involved in the image. Most commonly, one shoulder is rotated toward the camera. This position allows for a full range of head rotation. To facilitate the range of motion for the head with vertical rotation and yaw, the shoulder closest to the camera is frequently lowered. This tends to be a widespread pose because it promotes a relaxed look. Posing with the shoulders horizontal or with the shoulder closest to the camera raised creates an “attitude.”

When the arms and hands become involved, the composition and posing for the portrait become more complex. Because of the flexibility and size of the arms, their position within the pose can determine the success of the portrait. The posing process can use arm placements designed around poses that feel comfortable for the subject but still maintain a sense of style. For most portraits, it is advisable to avoid right angles at the elbows or wrists and the creation of vertical or horizontal lines with either part of the arm.

Hands are almost always viewed from the side; this slenderizes the subject and allows for graceful curves with the feminine hand and angular forms with the masculine hand. The exception to this would be when the hands are critical within the image. For group portraits, hands and arms take on significance as a means of expression. The pose determines whether there is a connection between the subjects and what emotion is communicated by the gesture. The hand interaction with the face can also imply gender. A closed or clenched hand tends to be more masculine while a relaxed or lightly curved hand has a feminine inference.

Unlike feminine poses, masculine poses avoid softening the pose with rounded shoulders or exaggerated shoulders, hips, and legs.

Like this post? Check out The Portrait, 2nd Edition by Glen Rand and Tim Meyer