The following is an excerpt from The Essence of Photography by Bruce Barnbaum.

A wedding photographer is generally one who photographs one wedding after another, catching the obligatory images of the bride, the groom, the bride and her family, the bride with her bridesmaids, the groom with his family, the groom with his best man, the moment the vows are made in front of the officiant, and the other expected wedding shots. But, like any other field of photography, there is room for real creativity here as well. Much the same can be said for portraits, which are usually done in a studio following well-known guidelines.

Clay Blackmore is a Washington DC-based wedding and portrait photographer who has gone against the grain, putting real creativity into his work in the process of building a national and international clientele. He does most weddings in color, with some black-and-white infrared for extra punch. Beyond that, he has fun with photography, engaging in things that most commercial photographers would rarely think of doing, even after an exhausting day of commercial work. His success is based on loving the work he does and loving the people he works with. With an approach that revolves around “pose, light, refine, and then shoot,” he says he can begin to work from the heart. “I simply don’t think; I feel.”

One of Blackmore’s favorite photos is an infrared image of a bride and groom walking on the beach in Laguna, California, the day after their wedding (figure 5–12). “You need to feel relaxed to create magic, so that’s why we photographed the couple the day after their wedding,” Blackmore says. Using a Canon 1DS Mark II adapted to take infrared images, and a 14mm wide-angle lens, Blackmore worked at high noon, with direct sun presenting a major challenge. “Instead of competing with the bright sun, we joined in,” Blackmore says. A strong Q flash off-camera, dialed up to full power, was the answer. He set the camera to 125 at f/16, and placed the flash six feet away.

“We started with a few posed images around the water’s edge, then we encouraged the couple to walk, laugh, and love. We began capturing the spontaneity between them,” he says. “We went low to shoot up toward the sky, creating dramatic backlighting. Just at that moment, the wind picked up the veil and WOW! A few seconds later, it was all over. The moment was there; we captured it. And then it was gone. That’s the beauty of photography.”

Blackmore was prepared. He knows that the veil of the bridal gown is one of the iconic symbols of a wedding. When the wind blew it into the air, he acted. He reacted instinctively; he didn’t think about it. In a way, it’s much like a basketball player working with teammates on a fast break—it’s fast, it’s in real time, and it’s utterly instinctive. At the same time it’s totally creative. Blackmore saw the moment and reacted. The sunlit veil is the obvious attention-getter in the image. But the kissing couple ties it all together in the most perfect manner. It makes a wonderful statement, and it does it with extraordinary pizzazz.

As Louis Pasteur noted, “Chance favors the prepared mind.” This quote applies perfectly to Blackmore’s image, and in so many ways to any fine image, from Henri Cartier-Bresson’s many celebrated Decisive Moment images to Edward Weston’s Pepper #30 to any other great image in the history of photography. It comes from a person looking, seeing, and instantly recognizing a superb situation. It’s not just being in the right place at the right time; it’s being in the right place at the right time, recognizing it, and responding quickly.

Another one of Blackmore’s favorite images was taken during a photography course he was co-teaching with his former mentor, Monte Zucker (figure 5–13). At the end of the course, Blackmore wanted to create a finale image to dazzle the crowd. He saw a bag of papier mach. flowers nearby and had the spontaneous idea to lay two faces side by side, in opposite directions, surrounded by the flowers. Blackmore shouted, “Monte, come up here and join me, I have an idea.” They began arranging the models and carrying out Blackmore’s vision. Blackmore had the idea, and together they were playing around with it. “We were really hamming it up to the audience,” Blackmore says. The two of them were on stage, so the large audience could not see exactly what they were doing. “It was a show. However, once the image flashed on the screen, I think we were as surprised as the 400 people watching the screens. It was exactly what we wanted: faces, and yes, feelings.” Sometimes the best photos can come from unexpected moments when you’re just having fun, Blackmore says.

This image is a perfect example in which intense coloration works perfectly because of what the image is. This is not a case of supersaturated colors being inappropriately employed. Rather, intense colors are used appropriately for an image that straddles the border between pure design and abstraction, yet is held together by the realism of two young, beautiful women. (It’s unlikely to have worked well with a couple of grumpy-looking old men. So the entire concept had to be carefully thought through for it to be successful.) The choice of colors enhances the image, putting a smile on the viewer’s face. Furthermore, you can trade virtually any color with any other, and the image would still be successful, and would still attract your eye. But also be aware that in the area of pure realism—the models’ skin tones—the colors are subdued and realistic.

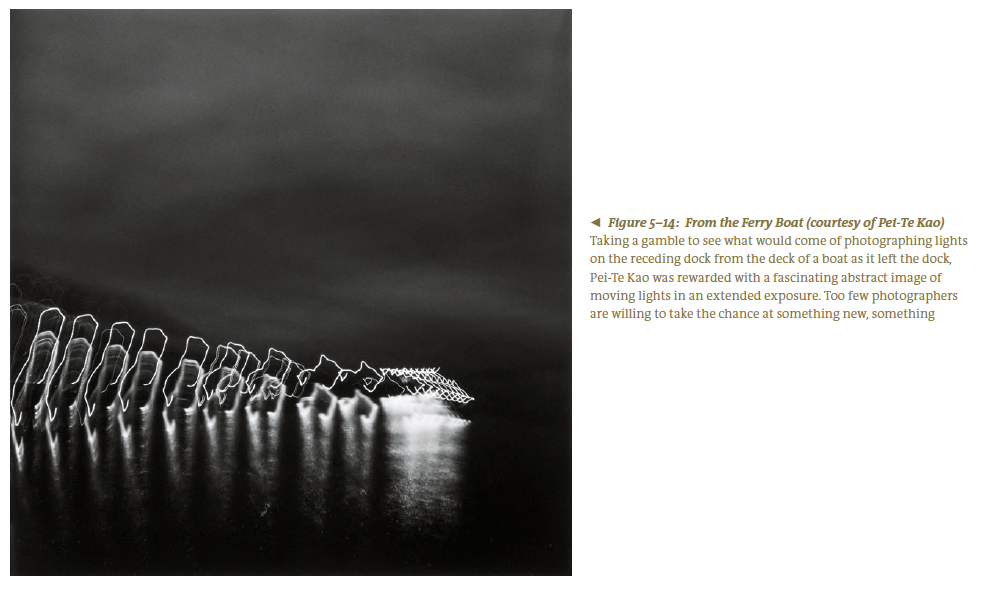

Another example of creativity in an unexpected moment comes from Pei-Te Kao (pronounced Pay’-tah Cow), a student and friend of mine. Not long ago she boarded one of the ferry boats traveling across the Puget Sound in the Seattle area. It was dawn, and still quite dark. As the ferry left the dock, she wondered what would happen if she aimed her traditional film camera at the lights surrounding the dock and in the nearby area. Of course, it would require a somewhat extended exposure, more than a second long. With the ferry boat engines pumping to the maximum extent, it would matter little if she placed her camera on a tripod or held it in her hand because the ferry boat was shaking quite perceptibly.

Under such circumstances, there are likely two thoughts that could go through your mind. The first is that there’s no point making an exposure because it will be out of focus. After all, Pei-Te had learned the importance of sharpness in photography, so making a hand-held photograph from a moving (and shaking) boat would be senseless.

The second thought is simply to try and see what happens. Most people stop at the first thought. Not Pei-Te. She considered both options, and decided to see what would happen. (Of course, today most photographers use digital cameras, so they can get instant feedback, but Pei-Te uses film, so there was no instant feedback. The results would have to wait for a later time.) The resulting image is a very fascinating set of squiggles and lines, which would be totally confusing and completely abstract if you had not already been told what you’re looking at, but it makes sense once you learn what it is (figure 5–14).

How often have you thought about making a photograph, but talked yourself out of it simply because you thought it wouldn’t work? I’m embarrassed to say that I’ve probably done it too many times, but I can also say that I’ve pressed ahead a few times as well. This is the essence of experimentation that can lead to lots of disasters, but also to a few surprising triumphs.

The photographs from Clay Blackmore and Pei-Te Kao are examples of creativity in areas of photography where few people expect or strive for creativity. This should be proof that creativity is hidden within any field of photography, and probably within any field in life, artistic or otherwise. It’s up to the creative mind to unlock it and set things off on a new road, one never previously traveled. Creativity stems from you, the creator, not from the subject matter at hand. That’s why some photographers are more creative than others, some artists are more creative than others, some scientists are more creative than others, some businessmen are more creative than others, some salesmen are more creative than others, and some teachers are more creative than others. The list goes on because creativity can be pulled from any field whatsoever.

It’s up to you to do the job as told and expected, or to invent new and innovative ways of doing it that may be far better, far more appealing, far more productive, and far more interesting to you.

This article on Creativity in Unexpected Places is an excerpt from The Essence of Photography by Bruce Barnbaum