This excerpt is from Within the Frame (10th Anniversary Edition) by David DuChemin.

It’s All Subjective

The subject of a photograph is not, for example, a child playing with her toy. That’s the subject matter. The subject itself is the emotion, thought, or intangible that you are trying to express through the image. In this example, it’s the play, or even childhood. Now choose a composition and a moment that best expresses that. The subject of the photograph can be simple: family, beauty, color, or wonder—that intangible thing that you responded to when your inner photographer said, “Oh! Oh! Shoot that!” or whatever it is your inner photographer says. Mine tends to be overly dramatic.

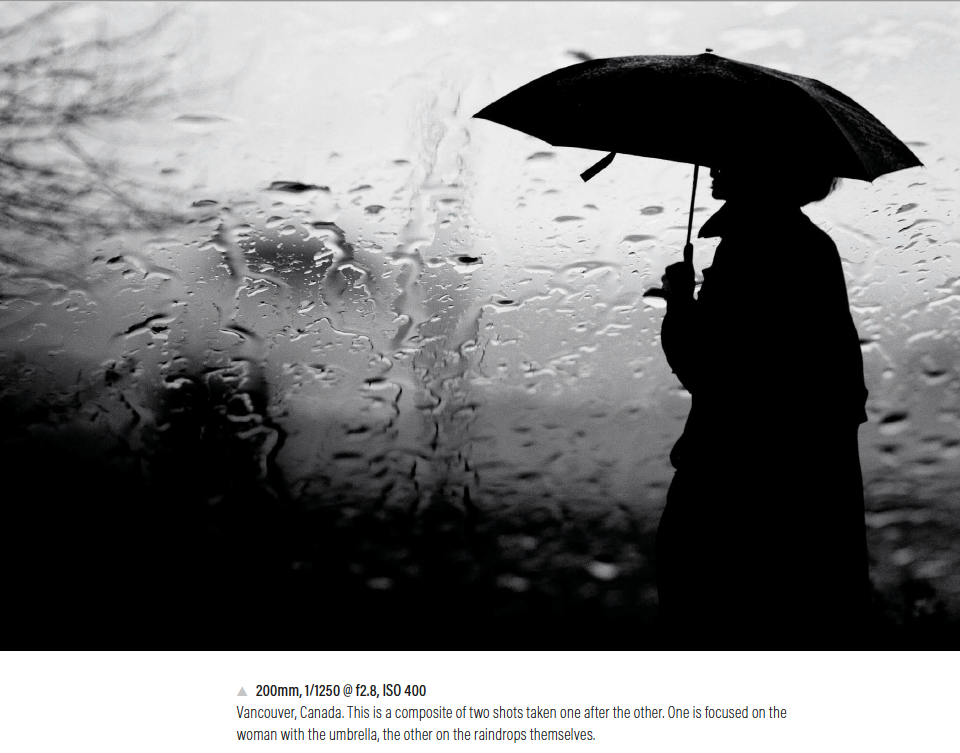

This is more than hair-splitting or semantics. Looking at things this way has profoundly changed the way I make photographs. It has given me a paradigm through which I can more easily identify the story I’m trying to tell. When I am shooting an image of people in the rain in Vancouver, and I understand that, for me, in this moment, the subject is not the people in the rain, the subject is wetness itself; I can shoot this in the way that best communicates wetness. I might choose to drag the shutter and blur the rain. I might choose to shoot through the window of a coffee shop and capture the people in the rain through the raindrops themselves. I might make sure I capture a couple with umbrellas or wait for a bus to drive past and shoot the resulting spray—all ways I can better shoot wetness. It’s an image of people in the rain, but it’s about wetness.

You might find a similar example on the banks of the Seine in Paris. Two lovers sitting on a bench kissing with the Eiffel Tower in the background. The subject of the image is—or might be—love, romance, intimacy. The objects that express that would be the lovers and the Eiffel Tower, icon of Paris, the City of Love. Seeking to best express the subject (love) through the objects (lovers), you will choose the best position from which to most clearly tell this story. You might want to make the subject more specific—like secret love—in which case you might choose to obscure the lovers a little as they kiss. Whatever your decision, it comes from understanding what the subject is and how it might best be revealed.

The Illusion of the Exotic

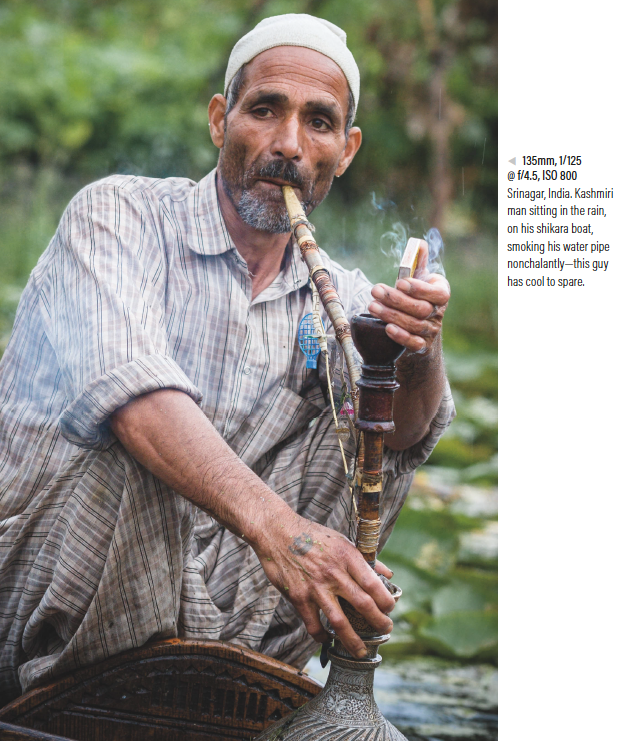

Making photographs of unusual things—exotic places or people, novel subjects—is the low-hanging fruit in photography. Making good photographs of those subjects, well, that’s a much harder task. While there is plenty of value in photographing the unusual, merely filling the frame with something exotic does not make it a good photograph; it makes it merely a photograph of the unusual or exotic. Whether it is a compelling photograph must be judged on other criteria.

Subject matter alone—separated from the craft of photography—rarely carries a photograph, and when it does, it remains merely a mediocre photograph of a fascinating subject, hardly the goal of most photographers. If by creating an image of the exotic you are hoping to say, “Look at this!” then by all means center it within the frame, set the camera to automatic, and take the photograph. But if you want to communicate something more, if you want to bring something new to the table and put your own thoughts, feelings, and personality into the image, then you need to photograph your subject matter as though you’ve seen it a thousand times and then suddenly see it in a new way. Does that make sense? You need to see it with something like spontaneous familiarity, moved by the actual subject matter and not just moved by your seeing it for the first time.

Seeing any of the iconic places in the world—the Taj Mahal or the Golden Gate Bridge—the immediate reaction is often to shoot it from the first angle from which we see it. We get so impressed by the size, the color, or the sheer exotic nature of it that all we want to do is raise the camera to the eye. After all, it would be impossible to make a bad photograph of something so great, right? Don’t ever lose that awe-inspiring reaction—there is a sense of wonder and curiosity that can infuse an image with similar magic for the viewer.

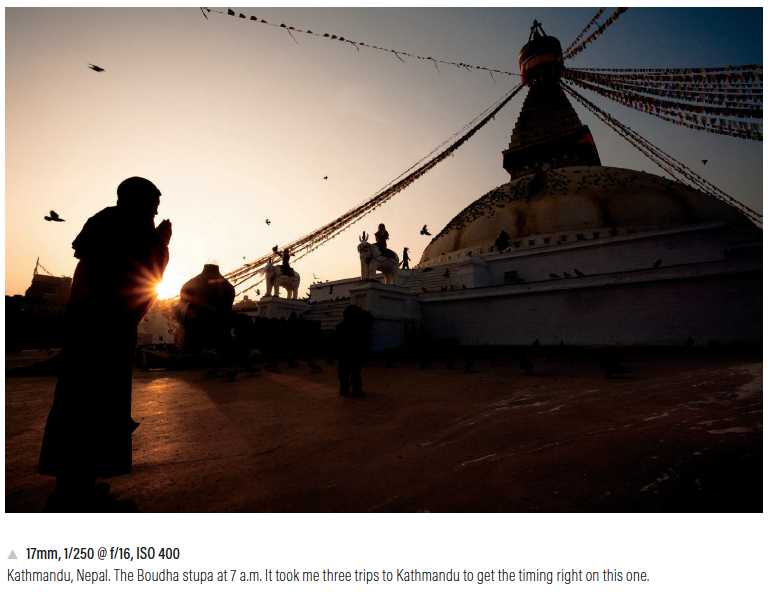

But between that initial wonder and it rubbing off on your audience lies your craft. The photographs don’t just happen, and if I want a good photograph of the Golden Gate Bridge and not merely a mediocre one, I need to both hang on to my wonder and explore it from every angle, and in different light, until I’ve found the angles or moments that best allow me to communicate my vision. It might mean trying many different lenses, returning at several times of the day, or waiting until a human element walks into my frame and hits his mark.

I’ve found it helpful to make a mental list of nouns and adjectives that describe my reaction to a place. In the case of something like a shrine in Cambodia, those words might be: architecture, serenity, monks, saffron robes, the search for the sacred, and others. It is those words that help me nail down what is otherwise a pretty vague and hard-to-describe reaction to a place. They help me become more aware of my vision and more able to create an image that best expresses it. Those words lead me to consider which elements are vital to the image and which tools of composition I need to use to help my viewers catch my vision.

As much as we are blinded by the exotic, we are equally blinded by our own familiarity. For the photographer shooting a new place, the challenge is to hold on to the wonder while becoming familiar enough to more fully capture something. For the photographer shooting something with which he is more familiar, the challenge is to rediscover the wonder and shoot with new eyes. Same coin, different side, and just as challenging. But either way, a compelling photograph needs to be evaluated on more than the novelty or exotic nature of the subject matter.