An excerpt from The Heart of the Photograph by David duChemin.

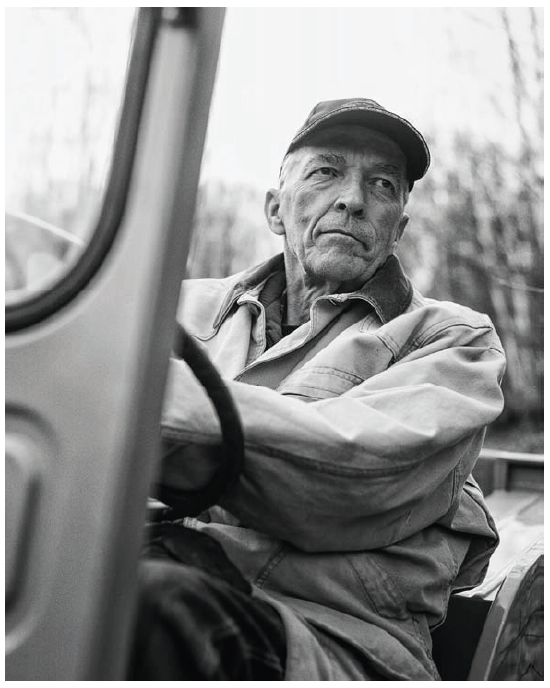

Richard Duchemin, 2011

Sometimes what we respond to in a photograph isn’t as much a matter of artifice as we would like to think. A photograph of Marilyn Monroe may not be well-composed or well-timed, but we respond all the same because, well, Marilyn Monroe. Of course, we know that the photograph could be more cleverly composed, that there are better photographs of Marilyn out there, but it’s irrelevant because we aren’t, in that moment, really looking at the photograph. And we’re not really looking at Marilyn. We’re looking at memory.

Many of the best photographs we make will be much more than the sum of their parts. They will be more than the lines and the moments and the colours, though of course these all have their part in making the photograph what it is. They will be powerful because nostalgia and memory are powerful. In the same way that mystery and imagination make a photograph stronger in our minds than it is on paper (because they draw from what we believe could be), our memory makes some photographs stronger because it draws from what we believe was.

I word it that way because memory is a tricky thing. It’s unreliable, for one. It’s unreliable because memory isn’t really about recalling events with objective accuracy; it’s about retelling stories that we create based on our own shaky and subjective recall of those events—stories that change with the telling. Why this matters is that photographs can tap into something powerful when they hint at these deeper memories. It’s the reason there is a booming industry in the retro or vintage plug-ins for Photoshop or Lightroom that allow us to emulate certain film stocks from eras that make us feel a certain way. As far back as when George Eastman was making and selling film at the turn of the 1900s, certain films had different characteristics—some with more grain, some with different colour casts and contrast. Different cameras and lenses had certain characteristics, too, and when someone now imposes a white vignette on an otherwise beautiful image made with a $5,000 camera that couldn’t make a white vignette if it tried, they are usually doing it to anchor the aesthetic of the image to a certain time period. They are hoping nostalgia will kick in for the viewer. The same is true of the borders some photographers put around their images—borders that were only present because of a certain kind of film. It’s a subtle nod to the nostalgia of predigital days.

Whether you choose to use techniques that are this heavy-handed or not, what is important to ask is this: “As powerful as nostalgia can be, is it enough?” Is the nostalgia of a white vignette or the colour cast that replicates a Kodachrome slide sufficient to carry the image? Before you answer, let me remind you (and myself as I write this) that it may well be. For some people, that is enough. But the images from back-when, the ones we love from our youth or even an earlier era for which we wish we’d been alive—they didn’t succeed or find a place in our memories because of that vignette or colour cast. The substance of the photograph was still the subject.

So when we rely on these effects, when they are not authentic to our means of working and are merely a style, we risk the possibility that people are not responding to the photograph itself, but only to their memories of similar snapshots; a copy of a copy that reminds them of something else. That’s not usually enough for photographers hoping to find and express a vision of something authentic. That doesn’t mean, however, that nostalgia can’t be used well and in authentic ways. Certain films, or emulations of those films, can add a layer of nostalgia over a story already well-told, creating more powerful photographs by tapping into the sense of “remember when.” Cinematographers choose colour palettes this way, anchoring the telling of their story to a certain time. When done subtly, it’s powerful, allowing us to access memories we forgot we have and the feelings we associate with them. The TV show Stranger Things is thematically rooted in the 1980s, and the colour grading used throughout that show creates a strong nostalgic connection for anyone, like me, who grew up in those years—or even for those who didn’t but who want to feel that sense of nostalgia. The show doesn’t rely on this nostalgia to succeed—it relies on great storytelling—but the nostalgic connection makes the story stronger, anchoring visual cues to memory and emotion.

Here’s the second idea I want to explore in a chapter that is rapidly becoming a bit of an outlier but also perhaps a thoughtful diversion: some of your best photographs won’t be very good at all, and that’s okay. Is it possible that the pressure on photographers to create work that others will consider worthwhile, or in which they will find merit, is stopping you from making images that will eventually have the strongest and most authentic nostalgic connection for you?

Indulge me in a moment of melodrama: If your home was on fire, which photographs (assuming you print them at all) would you grab on the way out? If you knew you were in your final days and had a chance to look at the photographs that, when it’s all winding down, meant the most to you, which ones would you look at? The perfectly sharp, the well-composed, the ones that got the most likes on social media or scored the best at the camera club? I doubt it.

I have a photograph of my father near me. He’s sitting in his beloved but ancient Jeep. A car man his whole life, he was the most “Dad-like” when tinkering with, talking about, or driving one of his projects. I made this image several years ago. I planned to make another on my next visit, but my father died in November 2018, before that visit could happen. This photograph matters more to me than you can ever know, anchored as it is in a lifetime mixed with the memories and regrets of a boy and his father.

When push comes to shove, the most important photographs of our lives will be the casual snapshots. And I’d be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge this and encourage you to take it to heart. Sometimes we get so focused on the perfect images, the clever images, the tack-sharp images, and the award-winners, that we forget photography can be so deeply human an activity, and we risk losing the profound and the poetic in pursuit of the perfect.

The question that suggests itself is a simple one: Are you photographing the moments and people most important to you? When is the last time you photographed your aging parents, your children, or Sunday lunches with the family? Will anyone capture those moments? Our memories are powerful, but we overestimate them. We credit them with greater abilities than they really have. They fail. They fade. We think we will always be able to say, “Remember when . . . ” when, in fact, one day we will not.