The following is an excerpt from David duChemin’s The Soul of the Camera.

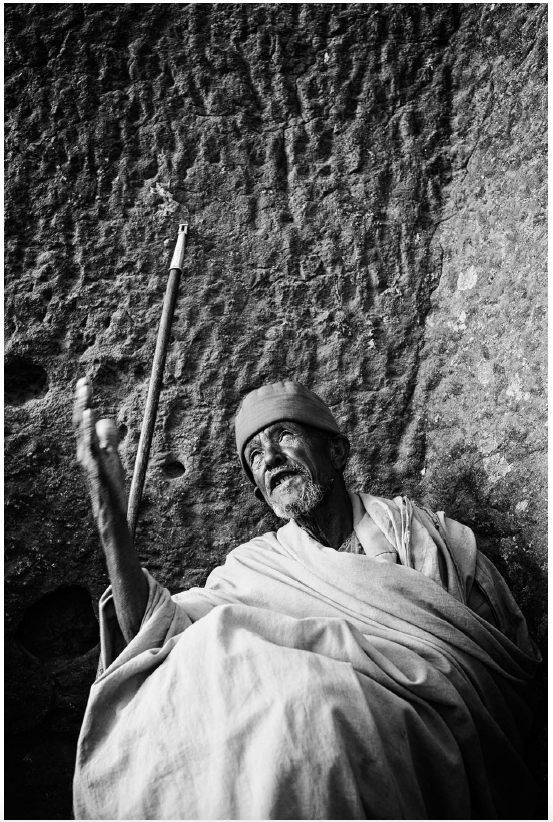

Lalibela, Ethiopia, 2012

Regarding the creative struggle, Columbian author Gabriel García Márquez has given some of the best advice I’ve ever heard: “Don’t struggle so much, the best things happen when not expected.” He’s advocating creative surrender. This is not giving up. It’s not resignation to forces stronger than we are that holds us back; it’s the acknowledgment of other forces pushing us in directions oblique to our expectations. Bigger directions. More interesting directions. It’s not compromising and settling for less. It’s recognizing a desire for something more than what we first imagined and not wanting to miss that. It’s seeing the flow of life and getting on board, not fighting it.

This kind of surrender—this receptivity—is important both in creativity and in life. There are times to fight like hell for the thing we want. And there are times to let it go. This kind of surrender is not about winning and losing. It’s not about pride or fear of paying the cost. No, this is about giving ourselves up to possibility and seeing where the current takes us. Because life is usually so much bigger than we think.

Outside of the studio (and to some extent, within it), life has a way of doing as it pleases without our permission. Never once has a scene unfolded in front of me on a dusty street in Ethiopia after seeking my consent. The beautiful creatures I photograph do as they will without regard for my desires. The people we photograph are their own souls with their own wills. And if we’re to remain authentic in our approach, the best we can do is bow to that will, see where it leads, and be ready with our cameras when the moment arrives. Life rarely acknowledges the inflexible; rather, it often has a particular scorn for it.

Fighting takes a tremendous amount of energy and attention. For most of us, the goal of what we do is not to win but to create. There’s a prevalent fight metaphor used by Steven Pressfield throughout his book The War of Art, but we shouldn’t lose sight of what he’s saying. Art itself is not the war. The battle is not against the elements “out there” as we create, but inside, against what he so appropriately calls “Resistance”: that voice that tells us to stay in bed rather than rise at 4 a.m. to get out for sunrise; that voice that reminds us how nervous we are about approaching strangers on the street; that voice that tells us to put off the personal project, delay printing our work, or second-guess the book project. We need to strive against those voices. Those are battles we must wage.

But that is not the fight I’m talking about; it is not to that internal foe I am suggesting we surrender. The fight worth surrendering is the one that takes us away from our best work, that drains us of our creative energy and our keen attention to the light, lines, and moments that make our photographs. It’s the fight against our expectations.

Creativity is hard enough without trying to match the force of life’s uncertainty with the force of our own assumptions and expectations. If the idea of surrender is too bitter a pill to swallow or if it feels too much like weakness, consider how force is used in the martial art of aikido. Force is not met with force but is instead redirected. A punch is thrown, but it is not blocked or stopped; rather, it is allowed to continue into space where the intended target once was. But that target has deftly moved to the side and is now pulling the punching arm of the fighter into a tumble that is fuelled by the momentum of the punch. It’s a much more efficient way of meeting force, especially when the opponent is much stronger. It is also elegant and graceful, like a dance.

I’m not comfortable with the idea of life as an opponent. I see my work with life as a collaboration. Perhaps it is also like a dance, though it often feels like a fight until I recognize that life is leading, and I submit to that lead, knowing I’m just new at this. In these moments of submission, my curiosity takes over and the constraints of a project, assignment, location, or scene begin to show me the way through rather than simply looking like obstacles. I once again hear Lao Tzu whispering, “What’s in the way is the way.” Submission to what is is the first step in seeing what is. When we fight against life with our expectations and our hopes for a particular photograph, we become fundamentally unable to see what is as we instead expend all our effort in looking for what we hope to be. Photographically, this tunnel vision keeps us from being receptive and observant, the two traits a photographer must always possess whether with or without the camera.

Submission is about going with the flow. It is not inactivity. It is not passivity. On some level, perhaps it’s the surrender of the left side of the brain to the right side, giving up the strictly analytical and the critical to a more graceful, open posture. To feeling what we are photographing as much as (if not more than) we are thinking about it. To understand submission as passivity or apathy would be unfortunate.

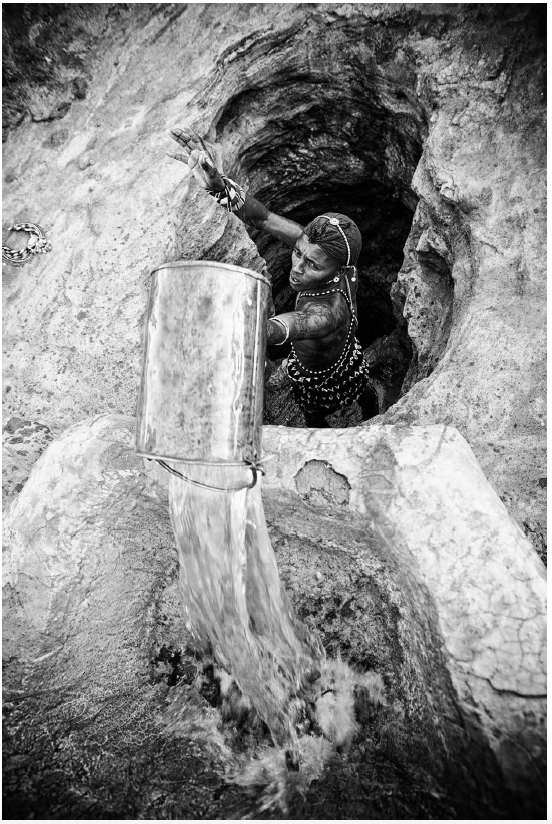

Kenya, 2011

In a bigger way, submission is not just going with the flow; it’s what allows us to experience flow in the first place. Flow is a state of being that is possible when the challenge of what we do and the skill level with which we do it are high and equal to each other. Flow doesn’t happen when the challenge is vastly too much for our skill: that’s struggle. Nor does it happen when our skill or craft is vastly more capable than our vision demands. That leads to repetition and boredom, as we have likely plateaued. Flow happens when our vision demands the fullness of our craft and pulls us into a state of extreme and almost unconscious focus.

That’s where the dance happens. That’s where we give up trying so hard to maintain control, and we bow to the wind and see where it takes us. Despite all this talk about submission, getting into a state of flow is not something over which we have no control. Getting there is hard work. Whatever our discipline, flow can’t happen without either craft or vision. There must be a challenge for it to happen, and a capability to meet that challenge. In those times when flow does not happen for me, I create a greater challenge by imposing greater constraints or by dreaming bigger. Creativity needs something to work with. Learn a new skill, work on new techniques, find something every day to inspire new dreams and directions. Flow happens on the back of hard work, and if it’s really flow, you probably don’t have to think too hard about it; you just have to let it happen, and keep working.

If it seems like I’m advocating two opposing points of view here—to both fight and surrender—it’s because there’s a place for both in the creative process. What I’m suggesting is that you fight to get to the place where flow can take over. Fight (work) for what you want, but be submissive or open to bigger things (like chance and possibilities you never considered) when it comes to the exact execution. For most of us, the thing we create is bigger than we initially expected, and it’s flow that gets us there.