Bruce Barnbaum took the time to sit down with us and answer a few questions about his prolific career.

Fifty years of photography is a big accomplishment. How did you get into photography initially?

Bruce Barnbaum: I picked up a camera—I think initially it was my brother’s camera—to show where I was hiking. I guess I was about 20 years old, in college. I wanted to show that I’m going through beautiful places in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, let me take some images. It had nothing to do with trying to be a photographer. My background is in math and physics. My goal in those days was to get a PhD in math or physics, and work as a researcher in either sub-atomic or celestial galactic physics. That’s where I wanted to be. I found along the way that students sitting next to me in graduate classes at UCLA were way ahead of me—I was not going to be one of the top researchers under any circumstances. I realized I wasn’t an Einstein or a Feynman. So I got a masters degree, and said, “that’s as far as I’m going to go.”

I got a job in programming at a defense-oriented place in the Los Angeles area, and I hated the job. It was not what I wanted to do, and for three years I was trying to figure out: How do I get out of this and into something meaningful to me? And yet, everything I could think of involved going back to school, and I wasn’t going to do that.

In the meantime, I was still working for a company called Aerospace Corporation in El Segundo. There was a guy who became friends with me, a fellow named Tim Travis, who had been the editor of his college yearbook, and he was into photography. He saw some of the hiking photographs I had made and said, “those are really nice,” and helped me try to think a little more about making better photographs. Then one day he said, “How about if I show you how to make black-and-white negatives and prints?” My response was, hell no! I don’t want to be in a darkroom, I want to be out hiking! I really have no recollection of what made me change my mind, but within several weeks I went back to him and said, sure.

Your interest got piqued. I’m sure you thought it was a new direction, a way to go deeper into something you were already doing.

BB: That was basically it. He showed me, and I realized, ok, that’s pretty simple. I went out and got an enlarger; I even got a new camera. I decided right away that I didn’t want to do black-and-white negatives with a small 35mm camera. I bought a 2¼” camera.

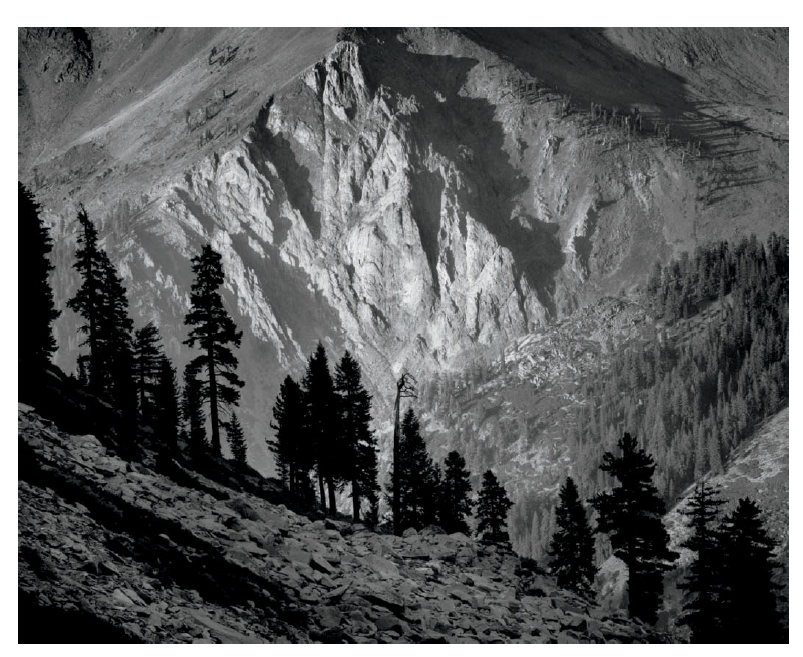

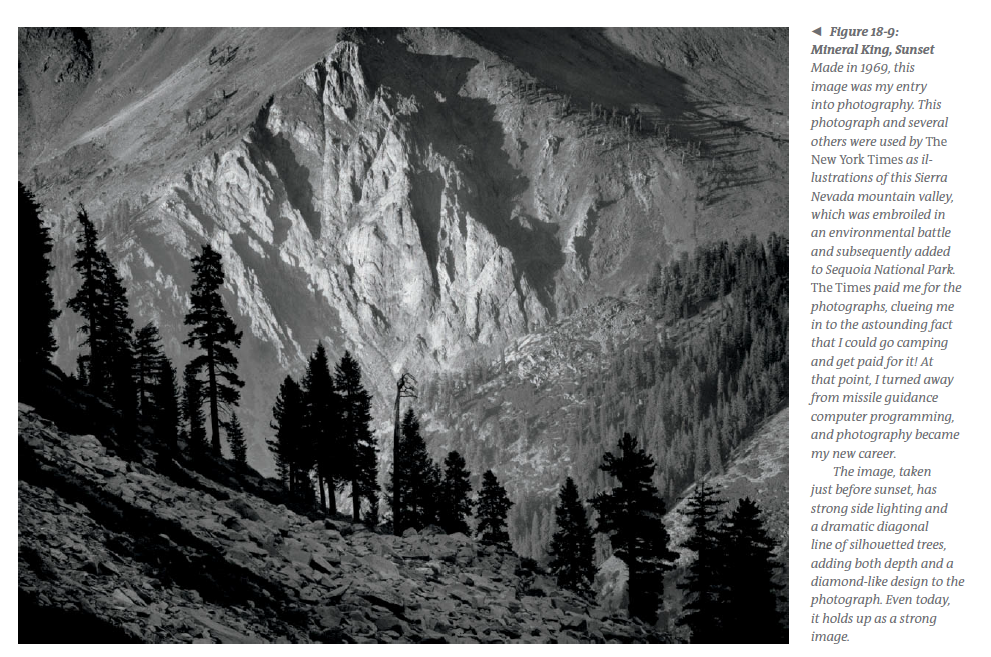

It was shortly after that—I was still working at Aerospace Corporation. It was 1969. I went to a place in the Sierra Nevada Mountains called Mineral King. Mineral King is a high mountain valley, surrounded on three sides by Sequoia National Park. Mineral King was right in the middle…It was at that point the center of a huge controversy between the Sierra Club on one side, who wanted Mineral King to be included in Sequoia National Park, and Walt Disney, which wanted to make Mineral King the largest ski resort in North America. So those were the battle lines. I spent an extended July 4th hiking some of the trails and photographing. With my newly found black-and-white understanding, I developed some prints from that trip, and then I did something that was really gutsy. I was living in the Los Angeles area at the time, and of course the Sierra Club is in San Francisco. I called them and said, “Do you want some photographs of Mineral King that I could donate?” I wasn’t asking for any money, I just wanted to donate, to say, I’m on your side of the battle. I expected them to say, “You’ve got to be kidding!”

Thanks, but no thanks.

BB: Thanks, but no thanks. “We’ve got a guy on our board of directors named Ansel Adams,” (which was the case, I knew that) and “we have three warehouses full of photographs of Mineral King.” The answer that I got completely surprised me—they said, “Oh that would be great, we have nothing!” So I said, “Okay, let me send you some photographs, and if you use any or send them out, let me know and I’ll re-supply them.” I have no idea how many I sent. That must have been early August, and that was the last I heard about it until November.

If, at that time in the universe, you bought a set of Britannica encyclopedias, you would then get, for the next ten years, something called “The Yearbook.” It had all the important things that happened in that year. In late November, around Thanksgiving, I get a letter from Britannica Encyclopedia saying, “Can we have permission to use your photograph of Mineral King that appeared in the New York Times?”

I promptly called the Sierra Club and said, “What the hell’s going on over here?” Shortly after they got the photographs, they were contacted by the New York Times wanting to do an article on the controversy. I said, “Weren’t you supposed to tell me?” At the time, I had no stamp on the back that said Bruce Barnbaum, or an address or anything; I probably wrote my name on the back and I probably wrote what trail I was on, but that’s it.

I called the guy at the New York Times and first said, “I want to thank you for using my photograph.” They gave me name credit, which was nice. He told me it was the August 18th edition of 1969. I found a place in Los Angeles that distributed the New York Times and got a copy of that edition. I suddenly come across a two-page picture, my picture, of Mineral King. The article started in the lower right-hand corner of the page, and then continued for the next eight pages. In the article there were several other photographs, some by different photographers, some were mine. I called that same guy back and said, “Do I get paid anything for this?” He said yes, I do. I gave him my address, and several weeks later there was an envelope with return address at the New York Times. I opened it right there, and I pulled out the check. It wasn’t very much, but remember, I’m working at Aerospace Corporation and hating the job, and I’m suddenly looking at a check. I said to myself, I could go camping and get paid for this? That’s where I’m going! It was that moment that I decided to go into photography.

So few people get to say that they went into photography because they were already making money off of it.

BB: It was at that point that I effectively stopped working at Aerospace Corporation. About 18 months later they noticed.

Of course, my parents were appalled. “You have a masters degree in mathematics and you want to take pictures? What are you talking about?” But they were extremely supportive, which was wonderful.

One of the great insights I had was that I realized immediately that while I wanted to photograph nature and the mountains, I didn’t have a name. Nobody in the world needed a photo by Bruce Barnbaum of a rock or a tree or a mountain, so I wasn’t going to make it that way. I needed to find something that was needed. I came up with the idea of architectural photography for architects of large buildings. I started photographing large office buildings in the Los Angeles area and I put together an album, actually using a wedding album, of 11×14 photographs.

All black-and-white?

BB: All black-and-white. I picked up the yellow pages and looked up architects, and literally started alphabetically in A. I called and said, “My name is Bruce Barnbaum, I’m an architectural photographer, can I show you my portfolio?” There wasn’t a single architectural firm that didn’t accept that and ask me to come in. I would sit on one side of the table, with a guy sitting on the other side of the table flipping through my book. Every once in a while, he’d stop and take a look at a photograph, and I was noting what photograph it was. I would come home and carefully study them to figure out why they were stopping there. Gradually I took the photographs that people were skipping out and replaced them with ones they were stopping to look at, until I got them stopping at more and more photographs. Eventually there was one firm that liked the photos and asked me, “What are your rates?” Of course, I had no answer to that, but I thought quickly and said, “Let me send you a rate sheet so you have it front of you.” Eventually, that same firm called me and asked me to do a job, which turned out to be the biggest job of my career. It was a gigantic shopping center southeast of Los Angeles, two million square feet, called Los Cerritos mall. I never got past B in the yellow pages.

When did you first start to see your particular style emerge?

BB: I never looked for a “style.” One of the things I caution against is for people to look for a style. You are you, and you are nobody else, and nobody else is you. If you’re trying to consciously create a style, you’re going to create a self-conscious style…I never tried to create a style; I tried to photograph the things that were of interest to me. Over a period of time, a style takes place and it’s inevitable. I tell people, “Don’t even think about a style. It’s going to happen.” It happens because you see things in your particular way. If I, and any number of competent photographers, were to photograph exactly the same thing, you’d get any number of different pictures.

When did your landscape work become your focus?

BB: It was my focus from the beginning. Through the Sierra Club in the Los Angeles area, I was named head of the camera committee. They did nothing for the Sierra Club. I proposed doing some weekend workshops, and the money would all go to the Sierra Club, which they liked. These led to my own personal workshops, which I’m still doing.

Things fell into place quite well in that short period of time.

BB: Somewhere in the late 70s, about ’77 or so, I was introduced to a gallery owner through a friend who was taking a bunch of my workshops. He started carrying my work—Stephen White at the Stephen White Gallery—and he sold some prints. He contacted other galleries across the country and got my work into seven to eight galleries around the country. That put me on the map.

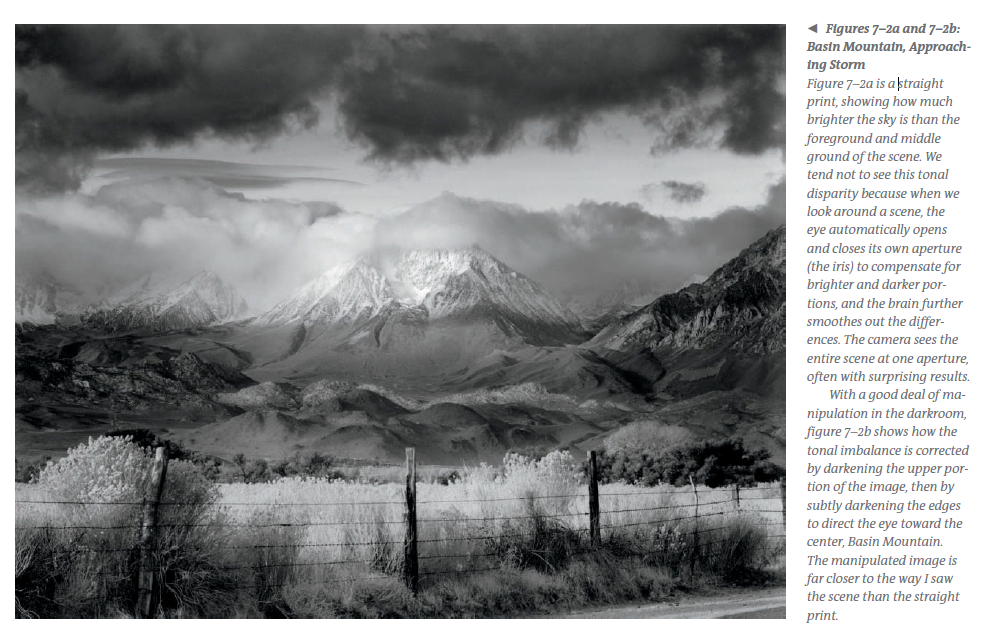

At the end of 1978, I had a show at the Stephen White Gallery, and for all I know, to this day, it could be the record-breaker for print sales at any photography show. The show was going to be from roughly Thanksgiving of ’78 until New Year’s Day of 1979. He sold about 275 prints, including 75 of one image: Basin Mountain, Approaching Storm.

(Please note, Figure 7-2a is not pictured in this article.)

Because it was a show at a recognized gallery, the LA Times sent a reviewer. He reviewed the show, basically wrote that Bruce Barnbaum is nothing but a second-rate copyist of Ansel Adams. He pointed to that particular photograph as an example. Since it was the first review I ever had, it was like a punch in the gut. And now I have to print 75 of that goddamn image because I had all these orders, and I was hating it. I didn’t even want to look at the thing. But by the time I had fulfilled all those orders, I could print the thing blindfolded.

When I finally finished all of them several weeks later, Steve called me again and said he had four more orders. I gritted my teeth and said, “Goddammit, if the first one doesn’t come out right, I’m not going to fulfill those orders.” My procedure in the darkroom is I print the negative, go from the developer to the stop bath to the fix, and then I could turn on the lights. I first inspect the print under fairly dim light because I’m coming out of that very dark environment, and then I put the print up on a sheet of plastic and put on better lighting and rinse off my hands and step back and look at it from a distance. I did that with the first print, and I stepped back and looked at the photograph to see if it looked good, and suddenly, I loved that photograph. I didn’t give a damn what that guy said. At that moment I came to grips with it.

About four years later, with a very eclectic show, I had another show at the Stephen White Gallery and the same critic wrote a review saying I was a great new artist. He pointed to Basin Mountain, Approaching Storm as an example of how good I was.

Did he not realize he’d reviewed it before?

BB: Apparently not. It was amazing. By that time I was thinking, whatever this or any other critic says: It’s interesting to read, but I don’t give a damn.

Have you ever read a critique that brings up points about your work that you’d never considered?

BB: Oh yeah. Several. I saved one in the LA Times. There was this sentence that just came out of the blue for me. It’s short: “It’s an exhibition that might have the persuasive power to give developers pause before ravaging special corners of our planet.” When I read that, I thought, I’m going to keep this. There can’t be any higher praise than that.

What are the biggest challenges you’ve had in being an artist?

BB: Shortly after I got into galleries, there was a big explosion of galleries across the country. As time went on, many of those imploded. There was a time when I had 12 or more galleries representing my work, in some of the key, critical locations like New York, Carmel, and Santa Fe—big art centers. I have no representation in any of those now. The galleries closed. But then books came along. My book, The Art of Photography, started as seven one-page papers that I handed out when I was head of the camera committee [for the Sierra Club]. I handed out one on exposure, and one on filters, and various things like that.

They were useful, and somebody suggested expanding them. Within about a year, instead of seven one-page papers, they were short seven- to eight-page chapters. At that time, somebody would say, “what do you mean by this?” and I’d look at the wording and say, “oh my god, that is worded poorly.” Sometimes someone would suggest a different wording, or another topic. Eventually with all these co-editors, it kept expanding. I was handing them out at workshops until it got to the point where it was too expensive to print at 75 pages.

It’s a textbook for your workshop.

BB: Effectively, yeah. At that point, I started charging for it, ten bucks. One day I got a call from a publisher that published textbooks for colleges. They wanted to publish The Art of Photography. My first question was, “How did you hear about it?”

I’d been invited to Alaska to do a workshop and a darkroom printing demonstration using the facilities at the University of Alaska. The guy who was head of the photo department was going to basically be my assistant because he would know where things were. I gave him a copy of my self-published book. This publishing company went to universities and colleges around the country to find books that they should publish, and this professor gave them Art of Photography.

They published it, and then wanted to publish a second edition. In the meantime, there had been a major change in the industry of photography because of the advent of variable contrast papers. It necessitated a major revision in the writing of the book. At that point they also demanded something else: They wanted me, because this is a book aimed at the academic section, to write questions and answers for each chapter. And I refused. I absolutely refused. That’s absurd. Any professor worth anything will write their own questions.

They went ahead with the second edition anyway, but they never met their audience. The book was not a dud, but only a few colleges ever picked it up because they had lazy professors who wanted questions and answers. After a while they discontinued the book, and I went back to self-publishing. I was mostly selling them through the workshops, and somewhere along the way I got a call from a guy named Gerhard Rossbach.

And here’s how this had come about: In one of my workshops in Utah, a backpacking workshop, a fellow from Heidelberg bought a copy of my book. He came back to Heidelberg and went to dpunkt [verlag; a publisher in Germany]. At that time dpunkt and Rocky Nook were the same thing, and Gerhard was the head of both. I got a call from Gerhard saying he wanted to publish the book. I said, “You’re crazy. There’s no sales potential in this book.”

Why did you think that?

BB: Based on the sales at my workshop. It was at zero. Gerhard thought we could put it together with photographs. The book was all text—it had no photographs. I’ll never forget: The book came out in October 2010, and I was in Argentina a month and a half later doing a workshop, and I get an email that said, “Are there any errors that you see in the book, because we’re doing a second printing.” I couldn’t believe it. I don’t know if Gerhard was surprised, but no one could have been more surprised than me. Within a short time I had the feeling that I had implicit trust in Gerhard and Joan Dixon.

How was your experience working on The Essence of Photography different from The Art of Photography?

BB: That was a non-technical book. That’s the one that currently I want to expand. I’ve written a number of essays, that could serve as chapters. Some were inspired by Guy Tal. He’s a wonderful writer and a wonderful thinker, and he inspired further writing from me. His book that Rocky Nook published, More Than a Rock, is fabulous.

What’s coming up next? Are there still things you want to do after 50 years?

BB: Nothing specific, but kind of everything. I always have new photographs, or sometimes old photographs to work with: some that I’ve printed and feel today I can do a better job; or photographs I’ve never printed and I rediscovered the negative. Projects for me just happen.

What do you think about changes in the photography industry in your 50 years of photography?

BB: I know very little about what’s happened industry-wide. I’m very narrow in my views. I have never been on any social media, even though I know from a professional business point of view that it would help me.

It seems that your career has been successful regardless of a lack of social media presence.

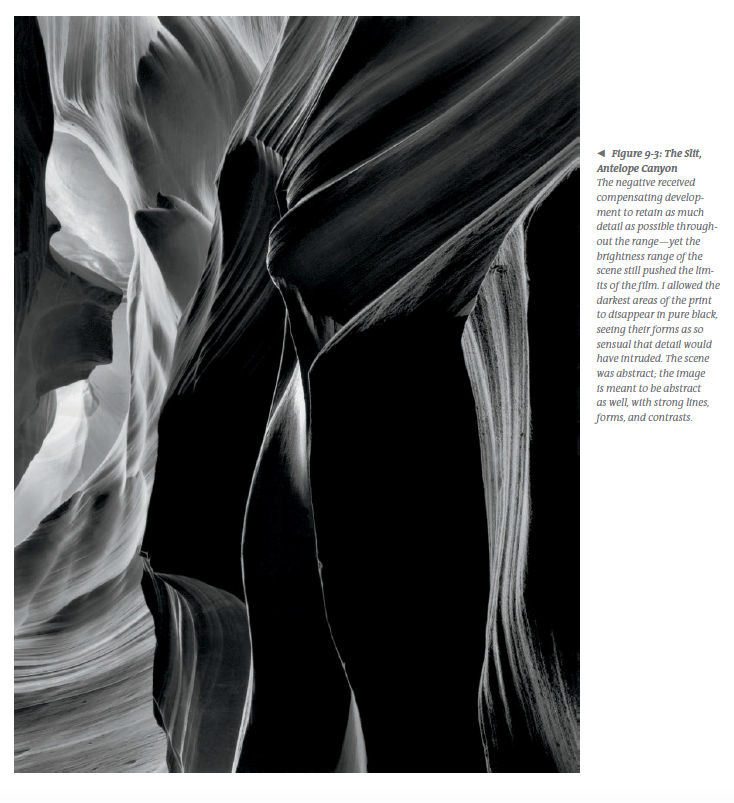

BB: It’s a struggle. I love the photography, but I hate every business aspect about it. I do like the writing of the books because there’s a mental component to taking pictures, and writing and reading about that is really quite interesting to me. In a new essay I’m writing, I start with: “Every photographer, whether they’re a beginner or not, has heard the phrase ‘it’s been done.’” Well, actually I had one. I started an aspect of photography that, to this day, I’ve never seen anybody whose work precedes mine. That’s the work on the slit canyons.

I walked into a place called Antelope Canyon on January 1, 1980, and it was unbelievable. I told you about my intended background of going into physics; when I walked into Antelope Canyon, I was surrounded by sandstone that struck me like a force field. Everything was swirling around. The moment I walked into this place with a friend, I literally could not talk. It was totally overwhelming. We started walking through this canyon and, without breaking stride, I said, “There’s my first photograph tomorrow.” I didn’t have my camera with me, and we were going to go home tomorrow. But when I went back to my friends and my wife, I said, “We’re not going back first thing tomorrow. I have just seen the most astounding thing in the universe.”

I started photographing that place the next day, and others of these slit canyons, which I’ve now written about. It hadn’t been done before. It was mine, and it was remarkable. The point of the article is that if somebody says it’s been done, that’s immaterial. It’s the insights that you bring to it. You’re going to see it in a different way, and it may be totally new, unique, compelling, and interesting.