This excerpt is from Authentic Portraits by Chris Orwig.

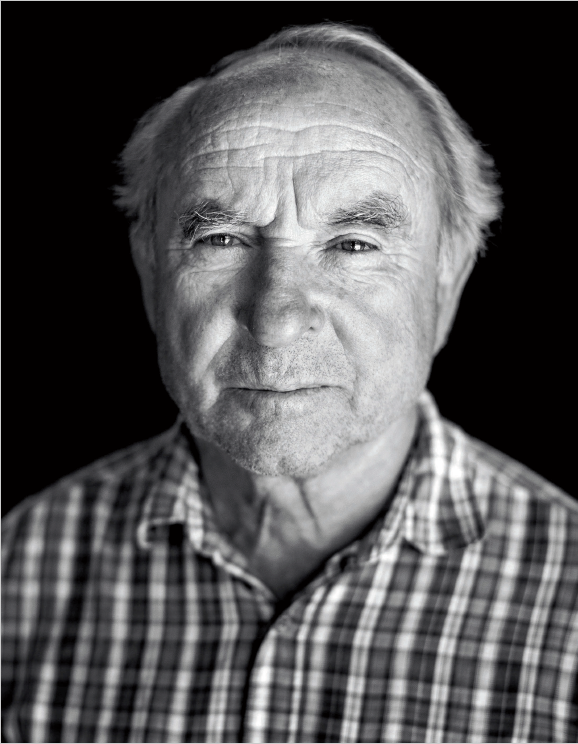

I had no idea how difficult this shoot was going to be. Yvon Chouinard was one of my heroes. I knew of him as a legendary climber, a passionate advocate for the environment, and the founder of the outdoor brand Patagonia. I met up with Yvon at the Patagonia headquarters to capture his portrait for a personal project I was working on. Yvon is a gruff and grouchy guy, but I had no idea how tough he was. I figured I could use my usual techniques (which I’ll discuss later in the book) to break through his rigid exterior shell.

We met outside his office and shook hands. After exchanging a few pleasantries and capturing a few images of him at his desk, he agreed to a change in location. We walked in silence to his old blacksmith shed, and he said in a monotone, “Let’s hurry up and get this over with.” Without much to work with, I started to capture what I could. Chouinard’s expressions were vague and blank—no emotion and nothing real. I kept trying to cheer him up. Nothing worked. There was no way I was going to get this old dog to smile.

SMILES AND WAVES

Of course, portraiture is not always sunshine and smiles. Some of the most powerful portraits don’t contain any smile at all. The human experience can be difficult, and portraiture, like all the arts, plays an important role in conveying that truth. A smile is a universal sign, and when it’s sincere, it’s a signal of happiness, welcome, and warmth. But no one holds a smile all day; it’s a temporary act, a brief moment in time. And so a smile is like a crescendo in music or the crest of an ocean wave. It does its thing and then it’s gone. It’s no secret that life is both wonderful and incredibly hard. The human experience is more than one constant grin. But when a camera is pointed our way, we seem to forget this. We forget that much of what we experience, like heartache or loss, is not conveyed with a smile. And certain character qualities, like thoughtfulness, resolve, tenacity, drive, and strength rarely involve smiling at all. And so, as portrait photographers, we capture the smile, but we also direct the subject in our search for more. While smiling portraits are nice, they are not always profound. When a subject smiles, he is usually trying to deliver what he thinks the photographer wants. It’s the photographer’s job to provide the feedback that, while smiles are good, so are serious and somber expressions. A portrait without a smile can make you stop, think, and feel in a unique and significant way. If a successful smiling portrait is the crest of a wave, a portrait without a smile is a view of the ocean in one of its many other moods.

MYSTERY AND COMPLEXITY

Think about the portraits you enjoy most and then ask yourself, “Are there any non-smiling and maybe even difficult portraits that have impacted my life?” Non-smiling portraits come in many forms. Some are overtly difficult, such as a portrait of a soldier wounded by a roadside bomb. In others, the emotion is a subtle subtext, as we see in the intensity and inner turmoil just under the surface of Van Gogh’s self-gaze. Or maybe it’s the sadness of John Lennon’s melancholy and peaceful face. Still other photographs provoke multiple emotions at once, like the haunting and beautiful photograph of the “Afghan Girl” by Steve McCurry, the despair-filled portrait of the “Migrant Mother” by Dorothea Lange, or the classic photograph of a scowling Winston Churchill by Yousuf Karsh.Once you start looking for these kinds of portraits, you find them everywhere. Smile-free portraits make up 90% of the greatest portraits of all time. When you stop to think about that, it’s a little odd, isn’t it? Why are they the ones that last? Maybe it’s because they’re complex. Without a big bold smile, the emotion may be hard to categorize. It’s not always easy to tell if a non-smiling subject is angry or determined, sad content, relieved or resigned. And this complexity is engaging. A mystery unfolds. The viewer is invited to pause and reflect. It’s almost as if, without a smile, the surface of the sea goes calm, time stops, and the portrait becomes a portrait about something bigger and more profound than a single moment in time. It becomes less like the crest of a wave and more like the fathomless sea. Of course, a smile can convey genuine happiness and joy. But when it’s automatic and not sincere, it’s often a defense. So to not smile is to invite both the photographer and, ultimately, the viewer into the moment. Encouraging and creating that invitation is where the risk and the craft come in. When we take the risk in a thoughtful way, it increases the odds that something meaningful will be conveyed in the portrait. These kinds of portraits do more than entertain. They help us to feel, and to lead better lives. They give us the opportunity to build empathy. They remind us that in suffering we are not alone. They provide us with the opportunity to broaden our emotional vocabulary so that we can better understand our own life and the lives of those we love. In other words, the depth and darkness bring harmony and light. Like Plutarch said over 2,000 years ago, “Music, to find harmony, must investigate discord.” Photograph the smile if it’s sincere. Otherwise, keep searching for the truth that is there. Honest photographs are best, and an honest scowl is better than an insincere grin.

SOMETHING REAL

Yvon Chouinard is an honest man. He doesn’t play the typical publicity games. He doesn’t run a business in a typical way. And there I was, photographing his blank face wishing that I could make him smile, but what I really needed was something that was real. So I stopped doing what wasn’t working and tried something else. I let go of my agenda and began to ask questions that I hoped would lead down a different track. Long before “being green” was popular, Yvon led the industry with environmental standards far ahead of their time. So I asked him why he was so passionate about the environment. His eyes came alive as he told me about a difficult visit to a remote and idyllic mountain town on the other side of the globe. He had visited this town 10 years ago and visited again just the previous month. What used to be pristine was now a polluted mess. Industrial pollution had practically wiped out the town. And all the children he had met 10 years before were now blind. Unclean water was the cause. As he said this, his eyes filled with rage and then calmed—but not so much that they lost their resolve. I lifted my camera and captured the frame that opens this chapter (pictured below), desperately hoping that I captured the fire in his eyes. But at the same time, I knew that whether or not the photograph turned out, that was okay. Because I had witnessed the truth of his soul.