Choosing the right lens or lenses is one of the most important photographic decisions you can make. Nothing affects the quality of a photo more than the lens. Many first-time buyers of DSLRs don’t venture past the basic lens included in the box. While some are reluctant to spend more money, others are confused by all the buzzwords or are overwhelmed by all the choices out there. It’s really a shame, because interchangeable lenses give you amazing scope for quality photography. You can take in vast sweeping scenes with a wide-angle lens; capture faraway birds with a telephoto lens; examine the tiniest detail of a flower with a macro lens; or record the perfect portrait with a prime lens. Anything is possible when you choose the right lens for the job!

New products are coming out all the time, and comparing specific lenses can be difficult. One of the first questions asked by beginners is, what lens should I buy? The answer naturally depends on your needs. Here are some things to consider:

- What is your budget?

- Do you have a specific need? Did you buy your camera with a certain purpose in mind? There’s no point in buying a long telephoto if you’re mainly interested in photographing stamps, for example.

- What focal length range do you use the most? One of the great things about digital cameras is that they record shooting data for each picture. You can then use an image-cataloging program to sort photos by focal length, aperture, and so on. If you find yourself using a certain range a lot, maybe it’s worth investing in a high-quality lens that covers that range.

- Conversely, what do you find yourself missing? When you take shots, do you always end up at the wide end of the lens, wishing you could go wider? Or do you find yourself at the long end, longing to be able to reach further? Think about what’s wanting in your best shots.

- What are your plans? Do you intend to build up a stable of different lenses so you’re ready to take on any photographic assignment? Or are you mainly interested in just getting one or two lenses that cover fairly general photographic cases?

- Do you want to set yourself some challenges? If you’ve got a zoom, try choosing a focal length, taping it down, and shooting only pictures using that setting. Imagine you’ve got a fixed lens in your camera and every shot has to be 28mm or 100mm. How does this affect your work?

Today, let’s talk about how to choose a lens for two popular subjects: people and landscapes.

Portraits

Is there such a thing as a portrait lens? Well, not literally. Any lens can and has been used for portrait purposes. However, for reasons of tradition, aesthetics, and practicality, certain lenses are more commonly used than others. The first consideration is focal length. Generally speaking, portraits are supposed to make the sitter look reasonably good. So unless you’re going for comedy value or you’re taking a full-body shot in the context of a given scene, it’s generally best to go for shorter telephotos than wider-angle lenses.

Really long telephotos are typically unhelpful because they require a large distances between the camera and subject. This can be fine outdoors, but it’s problematic in smaller studios where there’s simply no room to move further back.

The convention is to use a short telephoto, which has a focal length of at least 85mm on a full-frame camera. This focal length gives you a flattering perspective when shooting someone’s head and shoulders. Generally, 85mm, 100mm, and 135mm are popular portrait lenses.

Next, wide apertures are a good thing. A common portrait technique is to use a very narrow depth of field and focus on the eyes. This has a couple of advantages. It draws the viewer’s attention to the proverbial windows to the soul, and it tends to throw the background neatly out of focus. This is a great way to transform a busy and cluttered background into a nice abstract wash of color. Prime lenses with fast apertures like f/1.8 are good for this sort of thing, especially on full-frame cameras. Unfortunately, since depth of field is also dependent on the size of the image sensor, it’s harder to achieve narrow depth of field with a lot of mirrorless digital cameras.

Portraiture is generally done in a fairly controlled environment, like a studio. This is unlike the snap-and-grab world of photojournalism or sports photography, where time lost reframing an image could mean the difference between getting a shot and missing it. Accordingly, prime lenses with fixed focal lengths are typically favored for their high image quality—there’s less reason to go for zooms.

Manual-focus lenses actually make pretty good portrait lenses. There’s usually time for manual focusing, and the optical quality of many older prime lenses still holds up well today. In fact, ancient lenses with blurring around the edges or darkened corners can be fantastic tools for moody or evocative portraits.

Landscapes

The lenses used to shoot landscapes and outdoor scenes are as varied as the subjects themselves. But there are still some common points to consider.

First, landscapes generally don’t move very much. Obviously there are exceptions, such as scenes involving animals, cars, trees blowing in the wind, or hurricanes. But on the whole, the priority is to capture a scene, not to freeze motion. For this reason, landscape work frequently involves tripods and a contemplative, measured pace. This isn’t photography that cries out for image stabilizing, rapid autofocus, and huge apertures. Accordingly, tripods and manual focus are often the primary tools.

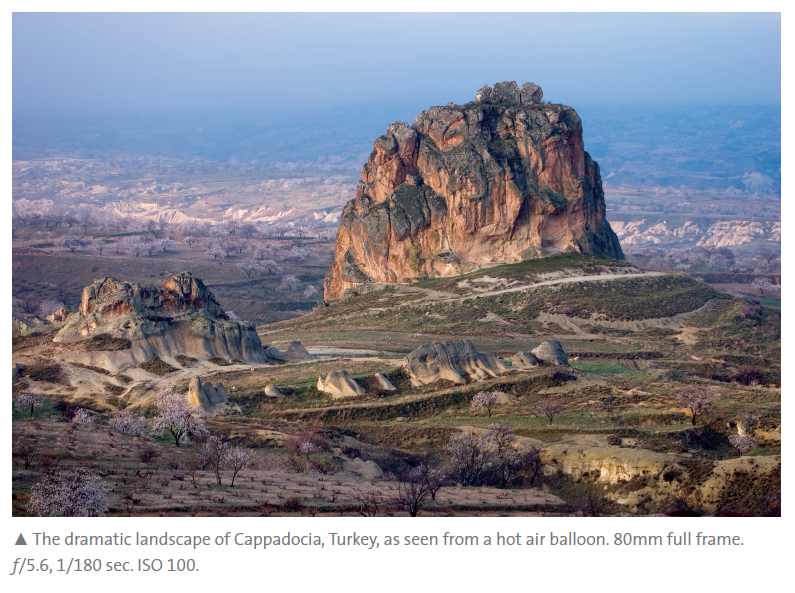

Second, when most people think of landscapes they tend to think of sweeping immersive scenes—photographs that transport you to another place or make you feel like you’ve stepped into the frame. This generally requires wide-angle lenses and extreme depth of field so everything is in focus.

Third, landscape photos are usually expected to be sharp. Painfully, crisply sharp. This, and the general lack of a need for rapid shooting speed, means that fixed focal length primes are common. Zooms don’t always confer the same advantages, and primes are typically sharper.

So, traditional landscape photography usually involves wider prime lenses, with an emphasis on sharpness over flexibility (zooms) or large apertures. But that shouldn’t mean that this is the only way to go.

For example, telephoto lenses are extremely valuable for picking out details in a distant scene. A wide-angle lens might record just banal clutter compared to the way a telephoto can flatten perspective, transforming distant hills into curved abstract shapes. A telephoto can record a sunset or moonrise in dramatic fashion, allowing the celestial body to be depicted in the image as a large disc rather than a tiny dot.

Of course, there are other choices. A backcountry hiker might go for a high-quality zoom for maximum flexibility, for example. It’s all very well to drive to a site in a cushy 4×4 (or, in the case of Ansel Adams, ride on a far more environmentally responsible pony), but a self-reliant hiker doesn’t have that luxury and may not want to carry a huge and heavy selection of various prime lenses. Legendary nature photographer Galen Rowell would go on epic hikes with a single 35mm camera and just a lens or two.

Next, the rise of digital has transformed a lot of landscape photography techniques. It’s now possible to stitch together multiple shots from the same scene, resulting in a vast and seamless panorama. Such panos can be assembled without extreme wide-angle lenses.

Finally, who says landscapes have to be pin sharp? Dreamlike, textured, and ethereal photos were the goal of the pictorialist movement of the late 1800s and early 1900s. There’s no need to be literal in photography.

This article was taken from The Lens by NK Guy. To learn more check out the full book here.