The following is an excerpt from David duChemin’s book, The Soul Of The Camera.

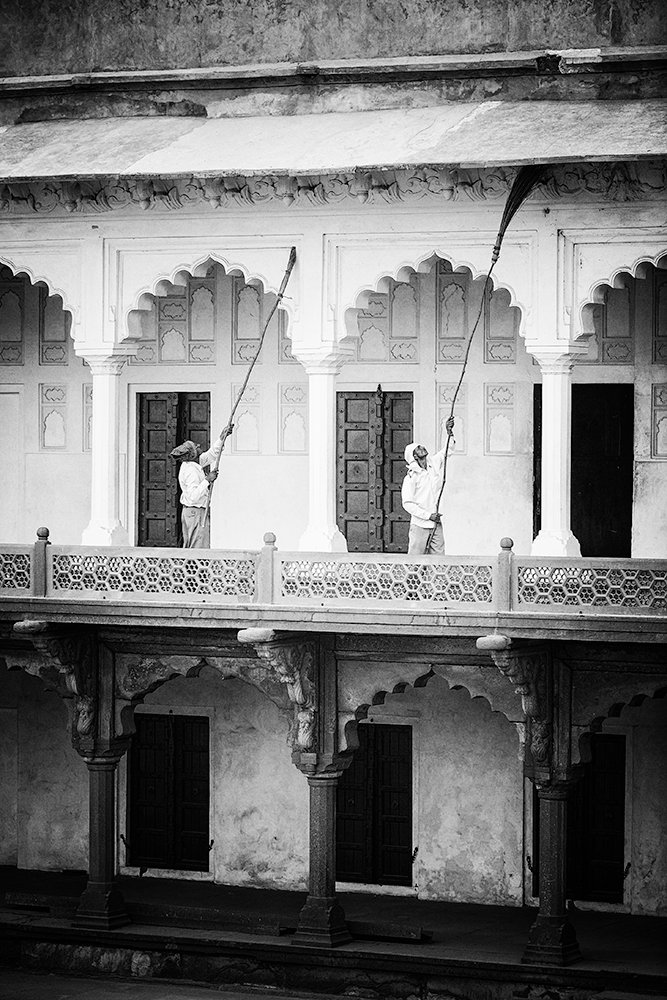

Agra, India, 2007

There’s a quote going around the internet that’s sometimes attributed to me, but I know I didn’t say it first. I believe I heard photographer and director Chase Jarvis say it, but I think even he was quoting someone. About the discipline needed to create art, he said: “It’s called art work, not art-f*cking-around.” I edited that a little bit.

Art can be many things and making it can take many forms. It can be spontaneous and playful. It can be tremendous fun, and when we’re in a state of creative flow, it seems effortless. But it takes work to get us to a place where flow can occur. It takes discipline.

Most of us don’t want to hear that, and I’m not thrilled to have to write it because the fingers that point back at me in blame for my occasional hypocrisy are my own. On most days, I’m as lazy as the next guy. I started making photographs because I loved it, not because I was looking for an activity to dominate my free time, my attention, and my affection. But maybe photographers are among the few in the arts who feel we’ve even got that option. After all, we’re told over and over again that cameras are now so good you just have to push the button. No one picks up the guitar for long without being quickly disabused of that kind of nonsense. They know it will take more than just playful tinkering to master that instrument and be able to produce something great. It will take years of work not only to be able to play the instrument, but to understand the language of music, to get a sense for what makes a good song, to get a sense for the possibilities.

I don’t think that play and work are opposites. I think they come together as discipline. Play is important, and I would never suggest we pursue photography without the love of it. But the reality is that even with the most naturally playful spirit, we have times—even whole seasons—when we’re stuck at a particular stage and it isn’t fun. But we plod on, knowing that if we stay static we’ll regress and we’ll regret the failure to move forward. That moving forward takes work.

Agra, India, 2007

I believe being good at anything, even those things we love most, requires discipline. Growth happens when we hit our limits (at the edge of our comfort zones, the furthest extent of our current ability), and it’s discipline that gets us past those natural boundaries. The word discipline has several uses. I don’t mean it in the sense of punishment. I mean it in the sense of a practice we willingly follow. I mean it in the sense that one can show up every day and get the job done, undistracted. I mean it in the sense that one studies and acts for a purpose beyond just the immediate gratification of doing something they love; if we only do what we love most at any given moment, we might just stay in bed all day. Not every footstep on the path to creating is a footstep we enjoy taking.

How does this apply? I think there comes a time when we declare our art—even if just silently to ourselves—a master in our lives, one we follow, one whose demands matter to us. We can certainly do it our own way and set our own rules, but we stick to those self-defined rules because we know they lead to a place beyond where we are now capable of reaching. And when we reach that place (where you begin to think of your art as part of your life’s work in some way, and not just a hobby that passes the time instead of redeeming it), we reassess the rules we’ve set for ourselves and then we continue.

Agra, India, 2007

We do the work. Every day or every week, we do it. We swallow our pride and find teachers in whom we see a spark and a skill beyond our own, and we learn from them. We practice and play and stretch our abilities and our imaginations. We go out with our cameras when it rains, and we go out when we don’t feel inspired. We study the work of others even when we’re discouraged and just want to wallow. We do the exercises and push through the frustrations with our limited technique, knowing that practice will advance those techniques and lead us to a new one and a chance, by having just become a master at some small thing, to become a beginner again.

It takes discipline to push past the good in order to get to the great. It takes discipline to keep at it for 10, 20, 30 years. And we keep working because it takes that many years or more to truly master something. I don’t know if it’s true that we’re not seeing any more artistic geniuses—those on par with Mozart, Michelangelo, or insert-famous-person-here—but I often wonder if the desire to master something so quickly, to “shoot like a pro” (whatever that means) within months of picking up a camera, isn’t a symptom of a larger issue in our culture or of our age. Mastery can’t be accessed via shortcuts, and it takes discipline just to stay on the path without taking the detours that are waved in our faces. There are no shortcuts that go where promised.

I like what Edward Weston was getting at when he said, “The fact is that relatively few photographers ever master their medium. Instead they allow the medium to master them and go on an endless squirrel cage chase from new lens to new paper to new developer to new gadget, never staying with one piece of equipment long enough to learn its full capacities, becoming lost in a maze of technical information that is of little or no use since they don’t know what to do with it.”

Discipline is what leads to the “know[ing] what to do with it.” It’s what brings the restraint to avoid the squirrel cage chase; in our case, that’s probably new cameras, new technology, and flavour-of-the-week post-processing. And far from being a restrictive force, discipline is greatly freeing. Choosing a path means being free of the burden of choosing from all the other paths that vie for our attention. It gives us the mental space we need to pursue what we’ve chosen (and if you’re like me, you need all the mental space you can get).

Maybe it’s not just discipline that’s required, but the courage or faith to believe that this path will actually lead somewhere. Sometimes it’s not obvious. Remember

Karate Kid, the movie? Mr. Miyagi, a Japanese man, teaches young Daniel karate. The first thing he has Daniel do is paint his house with very specific brush strokes—paint up, paint down—and polish the car with very specific hand motions—wax on, wax off. Daniel complains that he came to learn karate, not paint the house and wax the car. But then Mr. Miyagi teaches him to block a punch, and Daniel finds that the muscle memory to do so is already there, a result of the thousands of brush strokes and hand motions he’d put in while painting, sanding, and waxing.

That’s all we’re doing here: putting in the brush strokes and not allowing ourselves to get off track. I just want to remind you that it’s leading somewhere. Mastery is a long journey, pursued for the love not of mastery itself, but of the thing we master. For us, that’s the photograph.

Mastery can’t be accessed via shortcuts, and it takes discipline just to stay on the path without taking the detours that are waved in our faces.

Jodhpur, India, 2007

This is an excerpt from the book The Soul Of The Camera by David duChemin.