The following is an excerpt from The Film Photography Handbook, 3rd Edition by Chris Marquardt and Monika Andrae.

Cameras and Optics

If you consider how complicated our modern digital cameras are, it can be helpful and refreshing to remember that a camera is basically nothing more than a dark box with a hole in it and a shutter, with a piece of film or photo paper inside.

There are many cameras and optics nowadays that can let you experience the joy of low-tech photography. The less there is for you to adjust, the quicker you can shoot pictures instead of battling with buttons and wheels. See subject, point camera, shoot. That’s how easy photography can be.

The Box Camera

The box camera is one of the dinosaurs among the simple cameras on the market. It has been available for more than a hundred years. Provided you don’t try to get a collector’s item, it’s also generally one of the cheapest options if you want to take up low-tech photography. At flea markets or on Internet auction sites, you can get a working model for less than $12.

From left to right: Zeiss Ikon Box Tengor, Kodak Brownie Starlet, Agfa Synchro Box, Bilora Boy

A box camera is exactly what its name suggests—a box. This box has an opening at the front to let the light in and a film at the back. There are very few things you can adjust.

Sometimes there are one or two different sliding apertures behind the lens element, and even more rare is a small yellow filter that can swivel in front of the lens.

Most of these box cameras manage with a simple lens element, referred to as meniscus lens, which resembles the lens in a pair of spectacles. This lens has no or very little coating. This gives the results of using this type of lens their special charm by adding “dreamy” unsharp effects or circular lens reflections to the pictures.

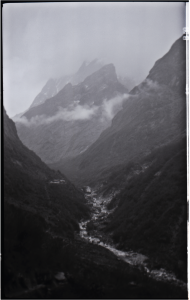

Landscape shot on Efke 50, taken with Agfa Synchro Box

Landscape shot along Annapurna Circuit on Efke 50, shot with Agfa Synchro Box

In terms of film type, the box camera is inseparably linked to roll film. Most box photographers use either type 120 or type 127. Depending on the model, the image formats are 6x9cm, 6x6cm and 6×4.5cm (film type 120), or 4.5×4.5cm (film type 127).

Although all box cameras are slow (they shoot at around 1/25 sec. and their small lens aperture doesn’t let in much light), we have not yet had a completely mis-exposed picture, even with medium-sensitive or low-sensitive films. You can safely leave your light meter at home when going on a photo excursion with the box camera. Being overly precise when composing your shot is also not recommended with most box cameras. The viewfinder crystals are often not positioned above the lens, so image elements you deliberately arranged at the edge of the shot may be cut off. The good old bull’s-eye perspective can help: If you put your subject right into the center of the shot, or at least leave a bit of a safety margin around the edges, you’ll usually keep the subject in the frame.

Most of these cameras are held at belly height for shooting, so you shoot from the hip. Take this as an incentive to listen to your gut rather than your head when taking snapshots with the box.

Diana, Holga, and Other Toy Cameras

It all started with the Lomo LC-A, a viewfinder camera with fully automatic exposure control. It was mass-produced in St. Petersburg, Russia, in the 1980s and had one thing, above all: faults. Due to the great number of its weaknesses, this camera was not very popular in its domestic market. Serious photographers who were able to afford alternatives chose to steer clear of it.

In 1991, some students from Vienna (Austria) came across the LOMO Compact Automat in a photography shop in Prague and started experimenting with it. They were delighted by the creative potential of its flaws and founded a photo initiative in 1992: the Lomographic Society International. They laid the foundations for a trend in which light leaks, strange contrasts, and a shifted color representation were no longer regarded as flaws, but deliberately used as creative design tools. In the wake of this trend, simple cameras, such as the Lomo LC-A (35mm) as well as the plastic Diana and Holga (both medium format cameras), experienced a renaissance.

Diana F+ and Holga 120GN

The Diana

The original Diana is a camera classic. It was produced en masse in the 1960s by the Great Wall Plastic Company in Hong Kong and sold on the American and European markets. The manufacturers originally specialized in toys and promotional gifts, which is exactly what the Diana was. The original price for a Diana was less than $10. The Dianas that are made nowadays for and sold by the Lomographic Society are much more expensive copies (although still very affordable by comparison to other cameras).

Just like back in the 1960s, the Diana is a simple medium format camera for roll film format 120, with one shutter time and three available aperture openings. The camera has three distance settings of moderate precision. So far, we have been unable to determine if it makes any difference whatsoever to the resulting picture where the arrow on the focus ring is pointing.

The Diana has always been made entirely out of plastic and manufactured so cheaply that it should really be classified as a disposable camera in terms of the material value, even though many modern disposable cameras have clearly superior optics. In contrast to the Diana, modern disposable cameras are also light tight. As if that was what it’s all about.

The lenses of the Hong Kong beauty contain simple meniscus lens elements with an image circle that is not wide enough to evenly light the picture in the 6x6cm frame. The viewfinder is simple, but sufficient for pointing the camera in the desired direction. There is no exposure counter. Instead, a red plastic window on the camera back helps you wind the film forward to the right place. If you do not want your image numbers exposed onto the film, you should cover this window with a bit of sticky tape when not using it to check the film transport.

Double Dresden. Diana on expired Fuji Astia, cross processed using C-41 process

Sounds dreadful, doesn’t it? Yet despite, or rather because of its flaws, the Diana is very charming. The pictures have a soft, slightly dreamy quality that you can hardly achieve via digital means. The too-small image circle of the lens causes natural vignetting, rather than the kind you add via image-editing software. If you deliberately or accidentally fail to wind the film-advance wheel far enough, this can result in double exposures, producing an interesting panorama picture of overlapping images. The Diana is now sold as a “system camera.” In addition to five lenses, there is a flash unit, different film masks, and other accessories, all made of plastic. Plus you can also use it entirely without a lens—with shutter lock—as a pinhole camera.

The Holga

The Holga, launched in 1982 by Hong Kong company Universal Electronics Industries, follows a camera principle very similar to the Diana. The Holga designer, Lee Ting-mo, created a camera that features partial unsharpness, possible color distortions, and dramatic shadows in the image corners. The case is also prone to lightleak. Holga fans know (just like fans of the Diana) that there is one thing they definitely will not get with their camera: technically flawless photos. But the Holga is still one of the most popular toy cameras and, by now, has become an object with a cult following.

The Holga is slightly more robust, but even more basic, than the Diana. The different aperture settings, which appear as sun, sun with clouds, and cloud icons next to a lever on the lens, work in only the later models (from about 2009), and you can basically only shoot at 1/100 of a second with one single aperture (around f/13). Vignetting and edge unsharpness are comparable to those produced by the Diana. Some Holga models offer one single luxury: They feature an integrated flash.

All toy cameras have one thing in common: In terms of photography, they are great levelers. Because there is practically no technology to master, photographers can concentrate fully on the imagery of the picture. The popularity of Holga and Diana extended beyond the Lomography movement. These cameras were used at universities and photography schools because they gave students an uncomplicated means for training their creative eye.

Both cameras are also great gateway drugs for getting into medium format.

The Pinhole Camera

Hanover, Marquardt International Pinhole (MIP)

Whether for hobbyists, experienced photographers or absolute beginners, pinhole camera photography is always an interesting exercise and an experience that sticks in your mind. Compared to pinhole cameras, even Holga, Diana, and box cameras seem to have extravagant features. Taking pictures with a pinhole camera means getting right down to the mere essence of photography and omitting pretty much anything except the laws of optics. You’ll experience how the basics of photography work: how a camera functions and how an exposure takes place.

Pictures from a pinhole camera are truly unique. They look ethereal and atmospheric, because unlike with most modern cameras, the pictures captured are not just a moment, but a considerably longer period of time. Pinhole camera photography reduces the camera to its absolute minimum. Even the simplest lens is omitted. Instead, the camera uses only a very small hole, a pinhole, to bundle the light. The resulting pictures show an infinite depth of field. All non-moving elements in the picture, regardless of their distance to the camera, are always represented with the same level of sharpness.

Old Continental Tire Company, Hannover, Germany. Marquardt International Pinhole on Neopan Acros 100.

4×5″ large format pinhole camera: MIP

Shots taken with pinhole cameras are long-time exposures. Depending on the size of the hole, the exposure time can be a few seconds, several hours, or even days. Because the tiny hole represents a very small aperture and lets in little light, pinhole photography is best suited for outdoor shots.

Hanover, town hall. Developed in Caffenol-C-H

If you buy a standard pinhole camera, the camera’s f-number is usually known. A smartphone app can help you work out the suitable exposure time. This type of minimal camera is available in many versions—from very basic and cheap (in the plastic universe of toy cameras) to noble wooden cameras with or without brass fittings. You can find something to suit every taste. Even digital photographers will get their money’s worth. Specialist camera shops offer camera body caps with a built-in pinhole (some even offer sophisticated vignetting) for many common system cameras.

You can easily build pinhole cameras yourself out of a tea caddy, beer can, bin, matchbox, pumpkin, and more. Sometimes all it takes is a rainy afternoon, a suitable camera/container, a pin, some black cardboard, sticky tape, and spray paint.

The Subjektiv

You can have fun with “planned accidents,” and not just with camera models. You can also go crazy with various lenses and adapters.

Certainly one of the more luxury models of pinhole camera is the Subjektiv, developed by Monochrom in collaboration with Novoflex. This modular lens has a focal length of 65mm and is an optical system with four interchangeable optical modules. It gives you the option of capturing light in many different ways, and each module has its own characteristic imagery. You get a pinhole aperture, a zone plate, an acrylic lens element, and a meniscus glass lens. There are also pinhole aperture sieves and photon sieves available. All models have something in common: They are not suitable for technological precision and optically perfect photography. They are used because their optical flaws, faults, and quirks contribute to a creative image composition.

Zone Plate

A zone plate is a plastic disk or foil with a printed pattern of concentric circles. It has similar properties to a lens, but the mechanism of the pattern is light diffraction instead of light refraction. A zone plate shows more pronounced irradiation than a pinhole aperture, which can create a creamy, impressionist-style image.

Lensbaby

Lensbaby 2.0 with accessories and Lensbaby Muse

Although the name Lensbaby now refers to a whole product range of different lenses or lens-type optical attachments (some of which show resemblance to the Subjektiv), we still associate this term with the original version: a flexible, bellows-like tube with a simple lens and interchangeable aperture inserts.

Our favorite Lensbaby, marketed in various versions as Lensbaby 2.0, Muse, or now Spark, is a selective-focus lens. You focus it by compressing the flexible tube and then bending it upward, downward, left, or right, until the small area of focus is where you want it. As you can see, the Lensbaby is also not for perfectionists. Precision is not its strength.

The size of the focus sweet spot can be adapted for the Muse model via differently sized aperture inserts. The Spark has a fixed aperture f 1/5.6.

Cloisters, Inzigkofen, Germany. Lensbaby Muse

at fully open aperture on expired Kodak Portra

160 NC

Gateway to the Cloisters, Inzigkofen, Germany.

Lensbaby Muse at fully open aperture on expired

Kodak Portra 160 NC

Squeezerlens

Cherry blossoms. Squeezerlens on Pentax 67

on Lomography Slide / X-Pro 200

The Squeezerlens (http://squeezerlens.com) follows a similar concept to the Lensbaby.

Using lenses that were predominantly not intended for use on a camera—for example lenses from old projectors or enlargers—Frank Baeseler, who died in 2021, created optics that produce a very special image impression. His son Sven has continued the business ever since. The usually very high-quality glass is mounted in a bellows, which has a bayonet on the other side to match the respective camera. Focusing is usually done by compressing or expanding the bellows.

Monika owns a Squeezerlens for her Pentax 67. This special lens is now available not only for medium format, but also for many SLRs and mirrorless system cameras.