The following is an excerpt from Harold Davis’s Creative Garden Photography

One of my favorite macro subjects in the garden is water drops. If you see a water drop and look closely at it, you’ll find magic, beauty, and perhaps even the ineffable. Water drops are worlds of their own. They follow optical rules of their own.

Inside these spheres you will find a play of light, focus, shadows, and colors. On the outer edge of the water drop, its “skin” plays with reflection and transparency. The reflection of the outer world is a distortion and refraction of our real world, but one that is recognizable.

Making a great water drop photo often involves figuring out how the outer-edge skin will relate to the interior world, and how the reflection of the outside world relates back to each of these elements. I like to conceptualize water drop images where there is a holistic harmony between all three elements.

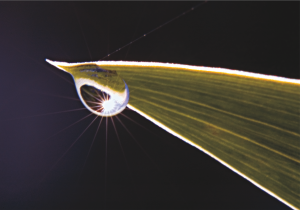

Figure 1—Good Morning Sun—When I am observing in my garden in the early morning before the sun comes up, sometimes I think what a miracle it is that the sun sets and rises each and every day. There’s that moment when there is already ambient light and color in the sky against the eastern horizon line, and then, slowly at first, and with increasing speed, the bright burst of the sun clears the line of sight and lights the day with its bright colors.

The world can be captured, as William Blake put it, in a grain of sand, and also in a water drop. One morning as I waited with my camera on tripod in my garden for the sun to rise, I decided to explore the day coming alive via a single drop of dew on the leaf shown here.

Quickly moving, the sun reflected in the water drop combined with the small aperture of my lens (f/32), creating a natural starburst effect. It’s great to be able to celebrate the return of the sun each and every day, whether writ large in a landscape or in a single drop of water.

Nikon D70, 200mm macro, 36mm extension tube, 1/15 of a second at f/32 and ISO 200, tripod mounted.

Approaching Water Drop Photography

When I approach a water drop, I think of the water drop as a jewel that encapsulates its own universe. Therefore, a field of water drops (when one is lucky enough to find them) is a field of universes, with each wet gem its own world.

It’s important to keep in mind that water drops are small, fragile, and constantly in motion. Outdoors in the garden, which is where I like to photograph water drops, they are subject to wind, and the vagaries of motion that can happen when I inadvertently brush my tripod leg against a connected part of the plant holding the water drop.

Light in the world around the water drop is constantly changing, and these changes are amplified by the optical distortion inherent in the spherical nature of a water drop.

You don’t find water drops all the time! Great water drops are rare indeed. The best water drops come after a rain storm, or are formed by the natural action of a heavy morning dew. But wind and evaporation from the rising temperatures following sunrise can quickly decimate even the most robust-seeming water drops. If you can call a water drop robust, which I don’t think you really can!

Perhaps contrary to one’s expectations, water drops from a hose, sprinkler, or spray bottle are quite different from “natural” water drops—although it may take quite a bit of observation to see the difference.

All in all, the water drop in the garden is a paradoxical subject. On the one hand, like any garden subject, garden water drops must be approached with serenity and in a meditative frame of mind. On the other, this is an unexpectedly rare and ephemeral subject, and when I see great water drops in my garden and photographic conditions are right, I know this is a subject that isn’t readily available very often, and that any given water drop may disappear before I can look at it twice in a small gust of wind. I try to keep both challenging aspects of water drops and photography in my mind when I head into my garden, and despite the challenges, this remains one of my favorite and most rewarding kinds of photography.

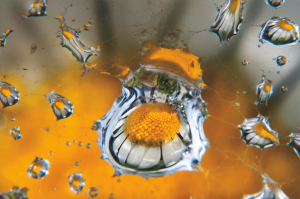

Figure 2—Isopogon formosus—Commonly known as the Rose Cone flower, the Isopogon formosus is a small shrub native to western Australia. Until it is in bloom, this member of the Proteaceae family has a dry, desert look about it. It isn’t until the wild flowers start to grow like buttons at the end of the evergreen-spiked branches that you begin to see how special the Isopogon formosus is. I love the curves and swirls in the intricate and delicate structures at the end of the pistils.

Bright water drops reflecting sunlight shimmered on this Isopogon formosus flower growing in my garden. The flower appeared against a dark background and I decided to balance out the exposure by bracketing three captures, one at 1/15 of a second for the background, and two “darker” exposures at 1/30 and 1/16 of a second for the center of the flower and the water drops.

Nikon D300, 40mm macro, three exposures with shutter speeds ranging from 1/15 of a second to 1/60 of a second at f/8 and ISO 200, tripod mounted.

Reflections and Refractions

A reflection is a mirror image in which left and right are reversed. A refraction is a curvature or distortion within a reflection, caused because the speed of light changes as it enters a water drop (or other optical medium).

As a subset of physics, optical science is largely about the way refractions and reflections interoperate and bend the curves of light that form our vision of the world. One of the fun things about water drop photography is that the photographer gets to make images that illustrate fundamental optical science in a very real-world kind of way. This is playing with light!

Most water drops are dome shaped, or even spherical. This means that they reflect an extremely broad view of the world around them, just as a fisheye lens does. The more refraction in the reflection, the less realistic the view of the world. In my opinion, the best water drop photography has elements within the water drop, both of reflection and refraction. In addition, refractions can manifest themselves as lens artifacts in the process of water drop photography, for example, as shown in Figure 3.

Keep in mind that the extent of reflection and the degree of refraction varies with extremely small shifts in the camera’s position. This is a function of the fundamental law of reflection, that the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection (see page 80). The most interesting natural water drop photos involve mixing reflections and refractions in unexpected ways, so I always try to be mindful of my camera’s position, and that very slight changes can make a very big difference when making these kind of images.

One final point about water drop reflections is that reflectivity combined with the wide-angle nature of a spherical water drop means that you and your camera are very likely to be in your photograph. Unless it is your intention to create a “selfie”—and this is usually not, or never, what I want to do!—you need to take care to avoid being the central attraction in a water drop photo. A telephoto-macro lens (see page 127) can help with this because it makes it much easier to get close to your subject without also being reflected in it.

Figure 3—Morning Grass—It rained hard overnight. In the morning, the sky was clearer with high scudding clouds. I went out early with my camera on tripod and crawled on my belly in the wet grass. As the sun came up, with my camera on the tripod, I made an exposure almost wide open (at f/5) for shallow depth of field. My lens was pointed at the rising sun coming through the water drops. You can see the lens rendering of the sun on the upper right of the image, along with refractions generated by the sunlight passing through the lens diaphragm.

Nikon D300, 200mm macro, 1/640 of a second at f/5 and ISO 100, tripod mounted.

Figure 4—Getting the Drop—This almost microscopically small water drop—shown here magnified many times life-size—formed at the end of a small blade of grass. The weight from the water drop weighed down the blade of grass.

I stopped my lens down for maximum depth of field (to f/36), so that both the water drop and the reflection of my garden within the drop would be in focus. If you look carefully at the drop, you can see a slew of other water drops on nearby flowers.

The drop stayed attached to the grass long enough for a small spider to attach a filament. But things never stay the same for long. The only thing constant in life is change.

Right after I made my photo, the water drop fell off its perch, and dispersed into the wind with water evaporating into the oncoming day, and the thin spider silk filament snapped.

Nikon D200, 200mm macro, 36mm extension tube, +4 diopter close-up filter, 1/5 of a second at f/36 and ISO 100, tripod mounted.

Spider Web Studio

The biggest challenge in garden water drop photography involves the fact that water drops are constantly changing and in motion. Extreme close-up magnification compounds the problem of motion. Making things worse from a technical perspective, usually I want to stop down the lens for maximum depth of field. This implies a longer-duration shutter speed, during which I need my water drop subject to keep very still to remain sharp.

The other possible technical approach to this problem—using a macro flash setup for primary lighting—brings a different set of issues, since the strobe will replace the refractions and reflections inherent in the water drop with its own—often blinding and unattractive—flash of light.

Meditating on this technical challenge one day in my garden, I glanced down and happened to see water drops clinging to a spider web in a sheltered corner of a rock wall. In fact, the water drops on the spider web seemed quite stable and out of the wind. Furthermore, there was space beneath the web for me to insert a flower, which could be reflected and refracted by the much more stable water drops.

Over time, I have had a number of “spider web studios.” I sometimes encourage their creation by bringing dead insects as thanks and tribute over to small spider webs in the making.

I look for these webs in parts of my garden where they will not be overly vulnerable to the wind, and where there is an easy way to add my floral “models” in a position where they will show well in their photographic “open call.”

Should you not choose to encourage spiders in your garden, it would be understandable. However, if you are interested in natural water drop photography, I encourage you to look for situations—such as spider webs—where the natural fragility and propensity to constant motion of the water drop is restrained by the environment.

Figure 5—Sunny Side Up—As I peered through my viewfinder at the water drops on a spider web, I was excited to see an entire flower refracted in the nearest drop. The focus was extremely shallow, even with my camera stopped all the way down for maximum depth of field (at f/36). So I decided to focus on the center of the refracted flower. If you look carefully, you’ll see that this area is in focus and appears sharp; however, there’s a softness to the refractions in the other water drops on the spider web. The flower beneath the web is completely out of focus and appears only as a bokeh-blurred background.

By the way, this image is also a kind-of “selfie,” as little as I like to admit it. Magnified, the reflection above the central flower shows the photographer (that’s me!) with tripod and camera, upside down.

Nikon D300, 200mm macro, 36mm extension tube, +4 diopter close-up filter, 1/20 of a second at f/36 and ISO 200, tripod mounted.

Figure 6—Spider Web Bokeh—The weather in the coastal range of the California Hills near my home in Berkeley was overcast with a low, clinging fog. It felt like being in the middle of a cloud. This is rare and wonderful weather for the natural water drop photographer because water droplets cling to everything. The fog creates a myriad of natural jewels, particularly clinging to anything that is sticky, such as a spider web.

It’s a veritable paradise photographing delicate plants and spider webs when gentle droplets stay put. This mostly occurs in the autumn, when spiders abound in the garden.

My idea in making this photo was to emphasize the out-of-focus patterns in the light reflecting from the droplets on this spider web. This attractive bokeh was emphasized by setting my macro lens to its maximum wide-open aperture (f/2). I carefully focused on the water drop refractions you see near the center of the image.

Nikon D810, 50mm Zeiss Makro-Planar, 1/4000 of a second at f/2 and ISO 200, hand held.

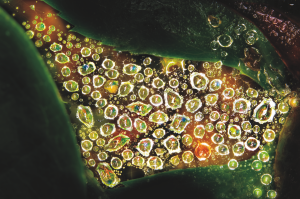

Figure 7—Interstitial—It rained hard overnight, and before dawn I rose with my camera to go out exploring. Heading out, my boots made squelching noises as I walked my neighborhood in the pre-dawn darkness.

Soon, the rising sun illuminated colored, autumnal leaves in a kind of pocket behind a spider web covered with water drops. The sunlight reflected from the colored leaves backlit the water drops and filled them with colorful refractions.

Once again, this was a “get down and wet and messy to make the image” situation. Hunkering in the mud, I lay on the ground, and positioned my tripod and camera.

Peering through the optical viewfinder as I adjusted, and the image gradually came into focus, I was excited to see an array of bright, prismatic colors created by the water drops.

I held my breath, hoping that nothing would move, and made six different captures at a range of exposure values, so that when it came to post-production, I would be sure to have the entire dynamic range of this incredible but miniature scene.

Nikon D300, 200mm macro, 66mm of combined extension tubes, six exposures with shutter speeds ranging from 2 to 15 seconds, each exposure at f/32 and ISO 100, tripod mounted.