The following is an excerpt from Chris Orwig’s book Authentic Portraits.

There is a spectrum and quality of light the eye cannot see. This is the light that the soul senses, detects, and knows. It’s the light that shines from a bride walking down the aisle. It’s the light that emanates from a young child who just got a new bike. It’s the keen brightness of an enlightened mind. It’s the light that fills you with warmth when you reconnect with a long lost friend. It’s the glow of gratitude on the face of a kid who finally found her lost dog. It’s the soft light of acceptance on the face of an old man who faces death and smiles at his family for the last time. This kind of light is ancient, powerful, and divine.

THROUGHOUT HISTORY, painters, poets, leaders, and common folk have struggled to describe it. It’s the kind of light that cannot be empirically measured or visibly seen. It’s more like a power, presence, or knowing. Here’s how Gandhi described it: “There is an indefinable mysterious power that pervades everything. I feel it though I do not see it. It is this unseen power which makes itself felt and yet defies all proof.” It’s not just Gandhi. Most of the major faiths describe the invisible and mysterious power as the divine. Most often, the faith groups use the metaphor of light—God is light. While these faith groups disagree on so much, light is the commonality shared by all. Across the globe, God and light go hand in hand. And so when we see that light shining from the bride, the young child, or the old man, I like to think that we are really seeing the substance of God, or at least some kind of divine light that connects us all.

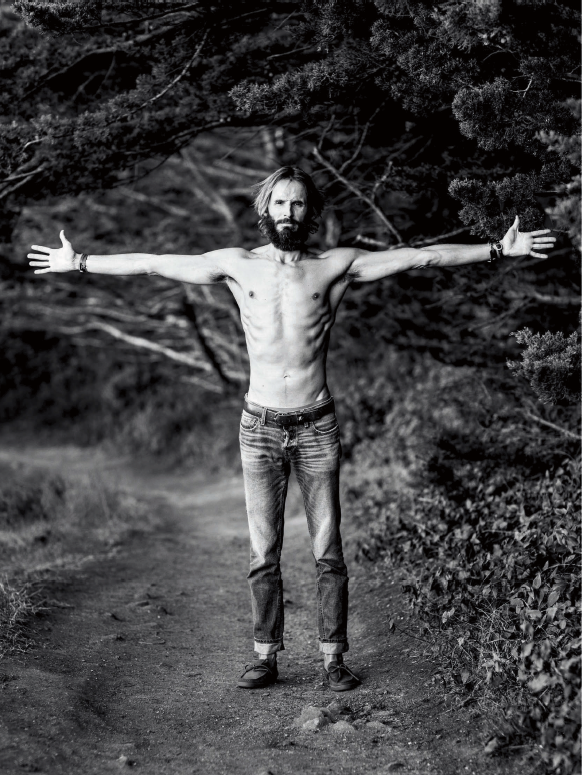

THIN PLACES In most faith traditions, this divine light shines through our good deeds and acts of grace and love. But it also shines through other things (animals, plants, trees), activities (music, art, dance), and places. The ancient Celts in Ireland had a great way of talking about the connection between divine light and place. Celtic mythology defined the separation of heaven and earth as “only three feet apart” but saw some places as “thin,” where the distance was even closer. Thin places were often wild landscapes, mountaintops, or where a river met the sea. What made a place thin wasn’t so much the geography but the experience there. The poet Sharlande Sledge explained, “Thin places are where the door between this world and the next is cracked open for a moment, and the light is not all on the other side.” A “thin place” wasn’t so much about what you saw, but about what you felt.

This Celtic notion of a “thin place” gives us words to describe the experiences we have in such majestic landscapes. When I’m out in the wild, I often feel small and am brimming over with a sense of awe. It’s the same kind of feeling I had when I saw my bride walk down the aisle, or watched the old man smile at his family for the last time. There is no other way to describe these moments except as a feeling of awe, wonder, mystery, and light. As I reflect on these experiences, I realize that as I was caught up in that moment, nothing else mattered— bills didn’t matter, time didn’t matter, I didn’t matter. My ego disappeared.

I once heard someone say that being selfless isn’t thinking less of yourself, but thinking of yourself less. And it’s in those moments of divine light where that happens most for me. I’ve come to realize that this is one of the main reasons I capture portraits: being filled with light helps my ego disappear. In more practical terms, working with a camera and connecting with another soul helps me stop obsessing and worrying about myself. The camera helps me feel small in the most beautiful way; it figuratively and literally takes the focus off me. In that moment, I lose myself and all I know is light. And that light restores and recalibrates my sense of truth, purpose, and joy. In a way, I take photographs in order to shed the excess baggage of having an overinflated sense of self. And I also take photographs to heal. With camera in hand, when I see someone else in a truly authentic and genuine way, their authenticity helps me bring forth my own.

Just as the Celts describe landscapes, mountaintops, and rivers as “thin,” I’d like to call portrait sessions the same. When a connection is made with camera in hand, it becomes a moment when that light shines through from the other side.

INCREASING YOUR INNER LIGHT But what do you do if portrait photography seems like it’s the opposite of this mystical Celtic idea? What if portraiture feels awkward or intimidating, or it makes you nervous? First, know that you are not alone. I feel this way almost every time before a shoot. My strategy to combat this anxiety comes from insight from my yogi friends.

These friends remind me of the importance of preparing myself. For them, the quality of a yoga session has less to do with the teacher, movement, or pose than with their own internal state. To get to a better state, I think about one of yoga’s most popular terms: namaste. This is a word spoken at the end of a yoga session. The instructor puts her hands together, bows, and says, “Namaste,” and the students return the gesture and phrase. What does namaste mean? While there are countless definitions and nuances to the term, my favorite is the one related to light: “The light in me recognizes the light in you.”

This idea of “light in me seeing light in you” is truly one of the great secrets to capturing better portraits. We must first look within, and only then can we see. We have to prepare ourselves if we want to experience change. Visiting a so-called “thin” place won’t work its magic if you aren’t open to it or in the right state of mind. It’s kind of like going to Yosemite and staring at your cell phone the whole time. Doing this inhibits the effect of Yosemite that John Muir once described like this: “Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees.” If we open our eyes, pause to sit down, and breathe deeply, the mountains and all their goodness will take effect.

So we first have to cultivate an inner light for it to begin to show up in our frames. What does it mean to cultivate your own inner light? Do you need to practice yoga, burn incense, or go on a mystical retreat? It surely wouldn’t hurt, but there is more than one path. For me, cultivating the inner light can be as simple as taking time to slow down, whether that’s by reading a book or going for a walk and leaving my phone behind. Other activities that bring clarity to my life are meditation, exercise, journaling, and doing something kind for a friend.

You’ll have to figure out what it is for you, but don’t neglect doing this. It will absolutely change how your portraits look and feel. Even though no one usually teaches this stuff in photography school, workshops, or books, trust me; it works. Try it for yourself and you’ll start to see a new kind of light filling up your frames.

And if you really want your portraits to shine, dig deep and do more than take a long walk or go to the spa. You might need to do some deep soul work. For me, this most often means facing and tending to my wounds. For example, a few months ago I was stuck in a rut. I felt hollow, lonely, and down. My portraiture reflected this void. Eventually, I lost all interest in taking pictures. I couldn’t figure out what was going on, and I could not get myself unstuck. I journaled, talked with friends, and read books, but nothing seemed to help.

Finally, I went on a trip to New York and something clicked. As I walked the streets of New York, the people and the energy there made me realize I was harboring disappointment, self-pity, and sadness from how my job situation had recently changed (long story short: my income from online tutorials dried up and I was angry and felt sorry for myself and feared what the future held). The fear, self-pity, and sadness were undercurrents I hadn’t yet admitted to myself. It was on this trip that I accepted the feelings and, in turn, accepted myself. I told myself that the emotions were valid, that feeling down was an acceptable response, and that I needed to reach for help. As I began the process of facing these wounds, I realized that the roots were deep; they went straight to my core. The real issue had less to do with income or work and more to do with ego, identity, and unresolved fears that I had been trying to ignore.

So rather than beating myself up, I sought healing and squared off with those issues with healthy doses of kindness and grace. Through the process of journaling, talking with colleagues, and bringing it up in therapy, my interest in portraiture came back. It was like I needed to do some soul work before I could reenter the game.

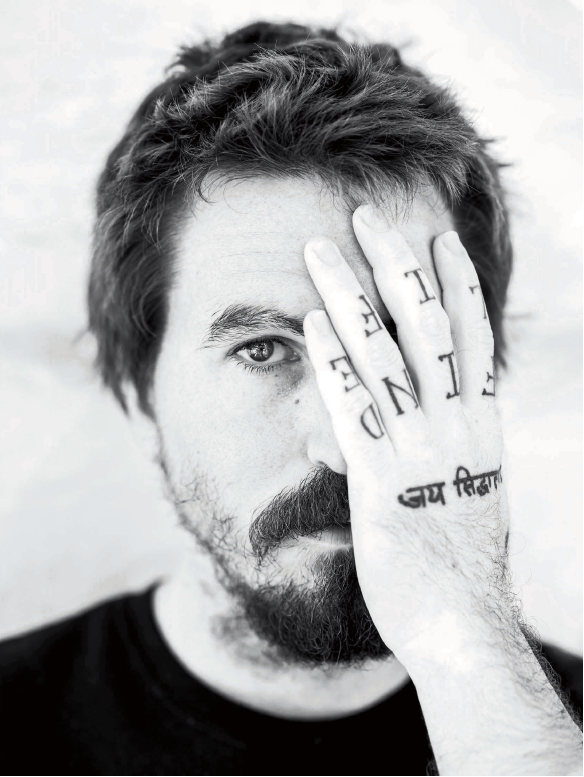

As I started capturing portraits again, I noticed that they looked and felt different. As I shot more photographs, I began to heal even more, and a new kind of light began to shine—a light that was vulnerable, honest, and true. Not only did I like the photos more, but they resonated with others more, as well. Nothing had changed with my gear, light, or approach. The only difference was what was going on inside.

Realizing this, I revisited those wonderful words by the poet Rumi: “The wound is the place where the light enters you.” And I listened again to Leonard Cohen’s lyrics: “There are cracks in everything. That’s how the light gets in.” Yes! This was music I needed to hear. The point wasn’t to hide or be ashamed of my own faults but to embrace them in an honest way. I had found the answer to Thoreau’s question, “How does the light get into the soul?” It’s through the cracks, imperfections, and wounds. When we face our wounds with kindness and care, it makes us more human and real, and it helps us to see others in the same way. Again, namaste: the light in me recognizes the light in you. And although I can’t literally see you right now, I imagine you reading this book and I see a bright light shining within your soul. It’s a bright, warm, and wonderful light that the world desperately needs. So do whatever soul work you need to do, so that we can benefit from the light that you shine.

The reward of all this, as you’re starting to see, isn’t just photographs that everyone likes; it’s that your life becomes fuller and more alive. When we approach portraiture with honesty, kindness, and grace, it has the potential to enrich and even heal our lives and the lives of those we come in contact with. So in this way, portraiture becomes more than pictures. It becomes a way that we all move ahead.