The following is an excerpt from Harold Davis’s Creative Black & White, 2nd Edition

It’s often not recognized that photography at night can produce wonderful results in black and white. As is generally true with black and white, if color is important to an image, it will work no better at night than in the day. In other words, spectacularly colored star trails do not work in the absence of color. At night, black and white requires strong composition with considerable contrast between light and dark areas. When I consider photographing at night in black and white, I’m looking for scenes that have a strong compositional appeal. In addition, the absence of color should add to the viewer’s appreciation of the scene. Someone looking at a black and white photo should think they know or feel something unusual about the scene presented. Perhaps there’s a sense that colors are more vivid than they would actually be if the photo were seen in color. Or maybe there’s an edge to the image that makes the viewer wonder about what they are seeing.

© Harold Davis w/ Nikon D300, 56mm, 52 seconds at f/4.8 and ISO 100, tripod mounted; converted to black and white using Nik Silver Efex Pro.

Trees in the Fog [above]—I came to photograph the view facing the ocean, but it was totally obscured by the fog. Turning in the other direction, I saw intense, orange street lighting coming through the trees on the other side of the parking lot. I knew this image would not work in color, because the quality of the street lights was very orange and made the scene look muddy. However, the shadows created by these lights towards the bottom of the row of trees were extremely visually intriguing. Here was a perfect situation for black and white at night!

© Harold Davis w/ Nikon D300, 52mm, 2 minutes at f/5.6 and ISO 200, tripod mounted; converted to monochrome using Photoshop Adjustment layers.

Point Bonita by Moonlight [above]—Point Bonita Lighthouse guards the Pacific side of the Golden Gate. Before modern navigational aids this iron-bound shore was known as a deathtrap for ships. Today, the lighthouse is visually interesting at night. You can see the lights of south San Francisco behind it. Most importantly, from a night photographer’s viewpoint, the light source—the lighthouse light—creates an entirely different world of shapes and shadows than can be photographed during the daytime.

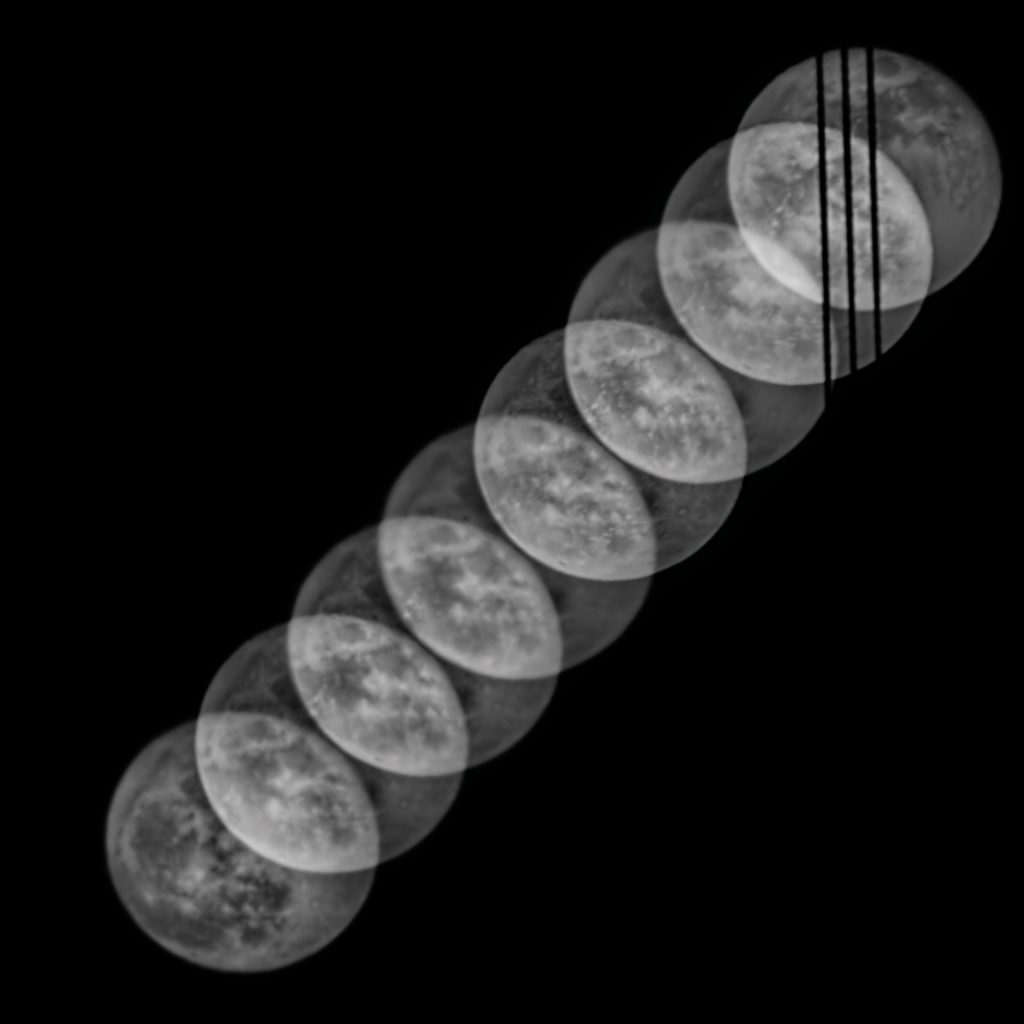

Lunar Progression [below]—This image shows the full moon rising from beneath the Golden Gate Bridge. You can see the risers of the bridge toward the right of the image where the moon is behind the cables. There is information on how I made this image below in the technical caption, but the idea was to time each exposure of the moon so that it overlapped 50% with the previous exposure. This creates the effect of the moon progressing and climbing upward in the sky. While the results are fairly simple, conceptualizing and executing an image like this takes quite a bit of planning and pre-visualization.

© Harold Davis w/ Nikon D300, 400mm, eight exposures, each with a shutter speed of 2 seconds at f/22 and ISO 100, tripod mounted; a total of 333 exposures made using an external intervalometer, with every 25th exposure used and stacked together using the Photoshop Statistics script on Maximum Mode, for a total of eight combined images used in the final image; processed to black and white using Nik Silver Efex Pro.

Wandering in the night, we are without the sense of clear sight that we usually rely upon. This causes many people to feel that they are adrift in a strange environment. Small noises can cause anxiety. Wind whistling through trees can sound like a howling gale. Phosphorescent eyes staring from a forest’s edge can be creepy. Black and white photos can pick up on this perceived anxiety, and produce images that are thought provoking and keep viewers on their toes.

With different light sources at night—moon versus sun, artificial light versus natural light, and so on—shadows become very different. Good night photography often renders the shadows of the night, and causes viewers to compare, consciously or unconsciously, the patterns of the night that contrast so deeply with the patterns of the day. Photographing the night makes us see things differently, and appreciate those differences so that we are better able to evoke the feelings of the exotic and ineffable—even with subject matter that might be commonplace in the daytime.