Composition for Moving Images – Shot Sizes December 13, 2016 – Posted in: Photography – Tags: cinematic composition, Composition for Moving Images, eduardo angel, extreme close-up, extreme long shot, Flicking Essentials for Photographers, full shot, long shot, medium shot

Composing shots for moving images is, in essence, very similar to composing for still images or paintings. But like any other craft, cinema has created its own visual principles with one fundamental intention: to effectively control what viewers see in the frame, how they see it, and when they see it.

The most basic shots are usually called primary shots. Among these shots are long shots, extreme long shots, full shots, medium shots, close-ups, and extreme close-ups. These descriptions can refer to any subject or location, but typically they are used in reference to the human figure.

Figure 1

The extreme long shot (ELS) can be used very effectively to establish the location and context for a scene (Figure 1). A common use of an establishing shot is when we see a character doing something for the first time (reading in bed or cooking in a kitchen), entering or exiting a building, or working in an office environment. The ELS is sometimes called the master shot.

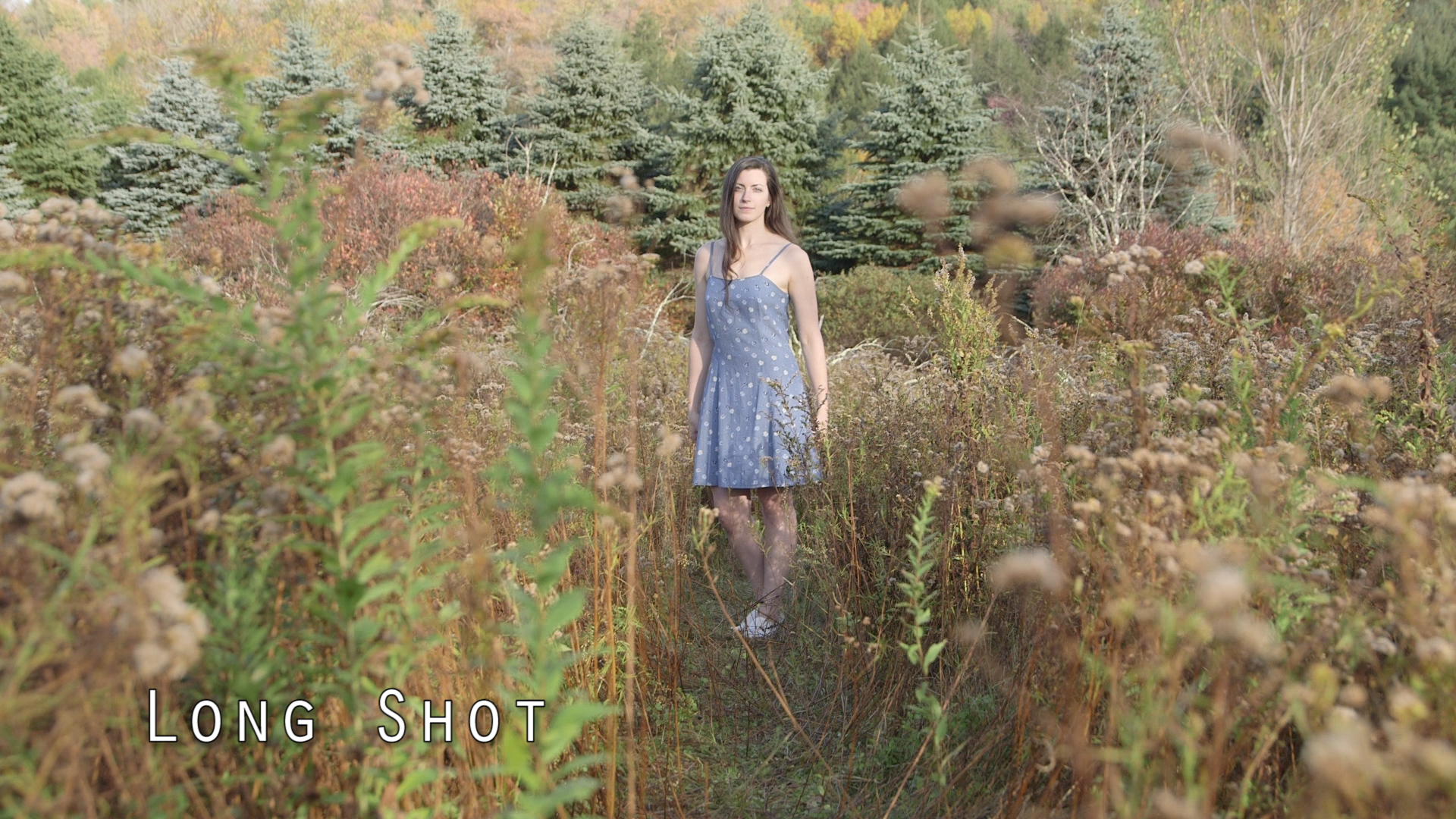

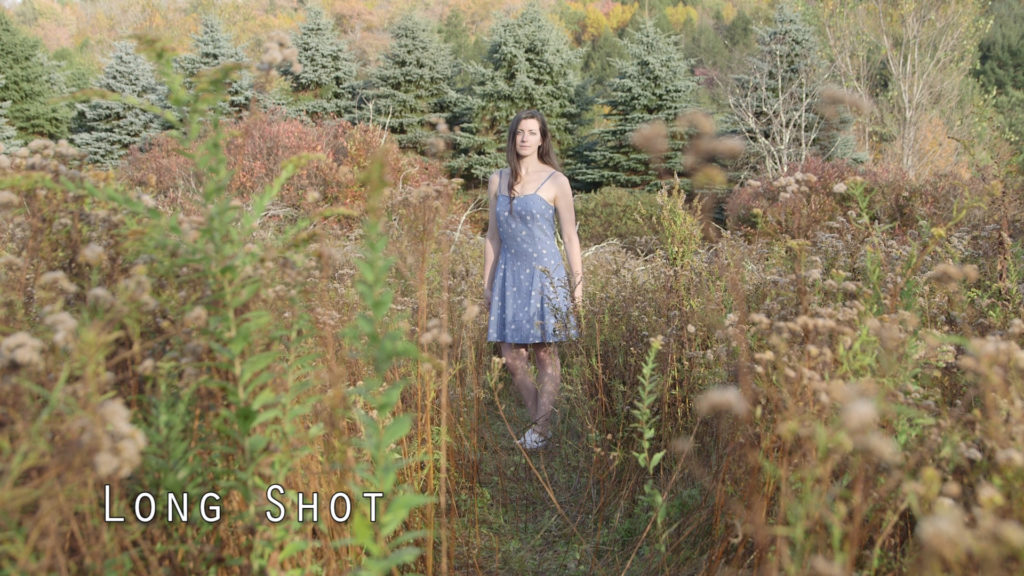

Figure 2

A long shot (LS) also includes a subject’s entire body and a large proportion of the surrounding area (Figure 2). The LS is also sometimes called a wide shot. It still gives the viewer a sense of location, but it also establishes the subject within a particular scene.

Figure 3

As the name implies, the full shot includes the full body, from the feet up to the top of the head (Figure 3).

Figure 4

The medium shot (MS) is arguably the most popular type of shot (Figure 4). It is wide enough to show an actor’s body language, but tight enough to include subtle variations in facial expression. As the camera moves closer to the subject, the field of view is reduced, visual information is removed from the frame, and the viewer’s attention is directed to the details that are left.

The close-up (CU) allows the viewer to have a more intimate relationship with the subject (Figure 5). Keep in mind that the wider you go, the harder it is to hide light sources, diffusion tools, microphones, and backgrounds. A key advantage of close-ups, whether you’re shooting a face or a hand, is that they allow for a lot more fine-tuning. You might not even need to match the exact lighting or camera angle from a wider shot.

Figure 5

The extreme close-up (ECU) is very useful for revealing key details that might be easily missed on a wider shot, like someone biting his or her lips or a teary eye (Figure 6).

Figure 6

All of these shots are used interchangeably to help illustrate or highlight particular details in the story. There are many other types of shots, including over-the-shoulder (OTS) shots, single shots, two-shots, group shots, Dutch angle (when the horizon is not parallel with the bottom of the frame), low and high angle, and insert (when part of a scene is filmed from a different angle than the master shot), to name a few.

Here are some useful tips about cinematic composition:

• For a number of reasons, sometimes matching wide and tight shots is very hard or time consuming. A simple trick is to make the angles and shot sizes different enough so the viewer won’t notice the difference on a quick glance.

• Sometimes getting one amazing master shot takes a lot more time than getting three or four less impressive but more useful shots. Choose the latter.

• A shot that doesn’t offer any value or relevant information to the story should not be done. Only shoot what you need.

• The more you practice and apply (and sporadically break) the cinematic composition rules, the more you will expand your visual vocabulary.

This article is from Filmmaking Essentials for Photographers by Eduardo Angel.

You can check out his newly released book here

PS. Save 35% with coupon EAFILM35