The following is an excerpt from Bruce Barnbaum’s The Essence of Photography, 2nd Edition.

It’s easy to look at things. We do it constantly without giving it much thought. It gets us through the day. But how often do you stop to really see what you’re looking at? By this I mean seeing something in depth, looking at it long enough and intently enough that you not only see that it’s there, but you actually study it and learn something about it.

In my book The Art of Photography, I discuss the difference between an average person looking at a crime scene and a seasoned detective looking at the same scene. An average person may see a room with some obvious blood stains and maybe a few other clues to a crime, but a detective would see a multitude of clues, some of which he would claim to be obvious. The average person would probably miss most of those clues entirely. This illustrates the difference between casual looking-and-seeing and in-depth looking-and-seeing. It also shows that there is a difference between an experienced and an inexperienced viewer. The detective has experience. He wouldn’t have spotted all of the obvious clues his first day on the job, but years of experience have sharpened his vision and taught him to look for details that the casual observer—or even the first-year detective—could easily miss.

A photographer cannot be a casual observer. A photographer has to look for the relationships within a scene, whether that scene is a studio setup, a street scene, a landscape, an architectural setting, or any other scene you can conceive of. A photographer has to see the relationships among the numerous objects in the scene in terms of form, line, tone, and color, and he must see those relationships within the three-dimensional vista in front of his eyes. He must recognize how forms, lines, tones, and colors in the foreground work with those in the middle distance and in the background.

A photographer has to notice that moving six inches to the right may create a better set of form relationships in the three dimensional field in front of his eyes. A photographer has to see how a portrait subject may stand out against either a black or white background, or if he or she would perhaps look better against a more complex interior, exterior, or landscape background that may say more about the person than a simple, nondescript background. A photographer has to see how the sunlight streaming through a dense forest could make a complete mess of a scene, negating any feeling of depth by turning everything into a blotchy cacophony of brilliant sunlight and deep shade randomly speckled on the trunks, branches, and foliage. But by simply looking in a different direction, that same light may produce clear separations between, let’s say, the backlit trees and the sunlight streaming between them. A photographer has to recognize that every type of light has its merits and its problems. Light that is perfect for one type of scene may be inappropriate for another.

Recognizing the difference between light that enhances a scene and light that detracts from the scene takes experience. Because a camera—whether it’s a traditional film camera or a digital sensor—records only light levels, the photographer has to learn to see light, and understand how light brings out or destroys the lines, forms, tonalities, colors, dimensionality, and all other aspects of a scene. Learning to see light requires experience because we’re really geared to see objects. That’s what we’ve done since we were born. It turns out that learning to see the objects in a given scene not as objects, but as light values and lines, forms, and shapes, and learning to see the relationships among them, is clearly not a natural act. It’s radically different. You really have to learn to see photographically.

This is difficult because our eyes do not see the way a camera sees. As you peruse a scene with your eyes, your irises open a bit to let in more light from the darkest parts of the scene, and close a bit to moderate the intensity from the brightest parts of the scene. So, in essence, you’re viewing every scene at multiple apertures. But when you snap the shutter on a camera, the entire scene is recorded at the single aperture you set. Unless you understand the technical aspects of controlling contrast via the process you have chosen (traditional film exposure or digital exposure), you may lose a lot of the information that you expect to see in your image.

The technical side of how you can fully record the scene is quite a challenge in itself. This is difficult not only in daylight, when you could be dealing with intensely bright sunlight and deep shadows, but also at night in a typical room in your home that is lit by a single lamp. In the latter situation, the inverse square law of light means that people farther from the lamp are much, much darker than those close by. You may not even notice the difference because your eye adjusts to a remarkable degree as it pans from the person closest to the lamp to the one farthest from it, but the drop in light is dramatic in the recorded image.

Complicating this issue further is the fact that a camera has a single lens, whereas your eyes see every scene with binocular vision, meaning that your left and right eye combine to recognize depth, which is not possible with a camera. Try looking at a complex scene with one eye closed and you’ll see that the scene tends to lose a large degree of depth. If you want to convey a sense of depth in a photograph, you have to learn how the one-eyed camera sees the scene under various types of light, and recognize which type of light helps bring out that depth.

Another tricky factor is that if your goal is to make black and- white photographs, you have to transform all colors to their equivalent gray level. While a red cardinal may stand out clearly in color against the deep green foliage of the tree it’s sitting in, both the bird and the leaves may be exactly the same shade of gray in black and white. It’s beginning to look like the best black-and-white photographer will be a color blind Cyclops! (It may help to start approaching your seeing with that thought in mind.)

You have to learn how to use filters when making the image to separate the two colors if you’re using film, or how to separate them in a photo-editing program later if your choice is digital. I mention this because whenever anyone brings up the names of the greatest photographers in photography’s nearly 200-year history, the list is still dominated by black-and white photographers: Ansel Adams, Edward and Brett Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Sabastião Salgado, August Sander, Julia Margaret Cameron, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Nick Brandt, and so many more. This is not just because photography existed for nearly a century before color film was introduced, but because many more outstanding black-and-white photographs have been produced even after the advent of color film…and of course, well before the introduction of digital processes.

None of this is easy to learn. Photography can be deceptively difficult. Some people may have innate talent, and it comes more easily to them. We’re not all created equal, as much as we like to believe that statement. Some of us are tall, others are not; some of us are brilliant, others are lacking; some of us are athletic, others are not; why, if you look around, you’ll notice that some are men and about an equal number are women. Now, I firmly believe that we should all be treated equally and judged equally, despite the fact that we’re really not created equal at all. Bringing this back to photography, some can learn to be outstanding photographers, and some can do it quicker than others, but it takes time to learn. And doing it well requires both learning and practice. So whatever innate talent you bring with you, it’s going to take some hard work to achieve your goals.

I have heard time and time again from people inquiring about my workshops, or from first-time students, that they “have a good eye.” Some people do. Most of the time they really mean that they can identify a beautiful scene. And while I hate to burst their bubble, it turns out that almost anyone can spot a beautiful scene. Very few people going into Yosemite Valley for the first time fail to notice its beauty. But most people take this to mean that they have a good eye. Not so.

Having a good eye means that you can recognize relationships between forms that almost jump out at you when you look at a scene from one location, but that don’t appear to be quite as compelling from a slightly different location. Having a good eye means that you can recognize when certain lighting or weather conditions make a scene quite extraordinary, whereas other lighting or weather conditions render it rather ordinary. Having a good eye means you can quickly spot an unusual and particularly interesting scene on a busy street corner in the midst of the typical nondescript hustle and bustle that occurs most of the time. Having a good eye means you can see when a specific type and direction of lighting on a person’s face, perhaps coupled with an interesting turn of the head, makes a powerful portrait, rather than the typical portrait we see from most commercial studios, or the portraits of “important people” giving an “important speech” shown on page 6 of your daily newspaper.

To create good photographs, you have to learn to see the light and the relationships within a scene. You have to learn to see with your two eyes the way a camera sees with a single eye and a single aperture setting. It would be great if the camera could learn to see the way you do, but unfortunately, that’s not an option.

Discovering and Developing Personal Interests

As you learn the ropes of seeing light and seeing relationships, you also have to find both your subject matter and your rhythm. Ansel Adams was drawn to the land, and more specifically to the mountains, and his best photographs are undoubtedly his powerful mountain and landscape images. He may have been a good portrait photographer, but it’s unlikely he would have been as good as he was with landscapes, and he probably wouldn’t have built the reputation he did. August Sander may have been a good landscape photographer, but it is his portraits of working-class Germans that are astounding, perturbing, penetrating images. These photographers and all of the other great photographers were drawn to specific subject matter that had heightened meaning to them, and they walked away from other subjects. That’s why their work is so outstanding.

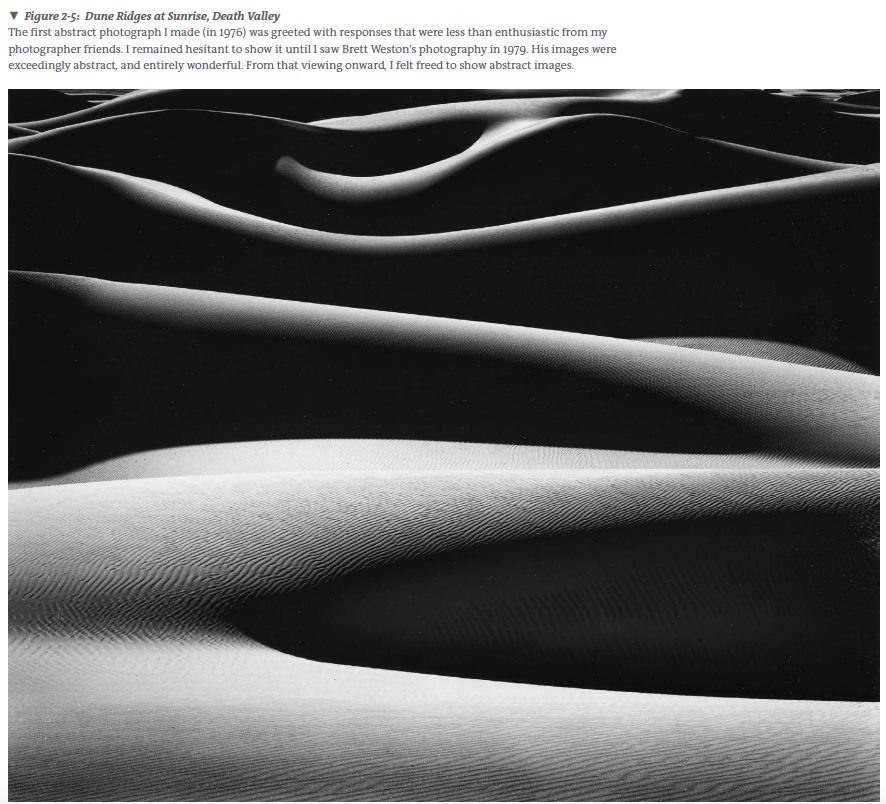

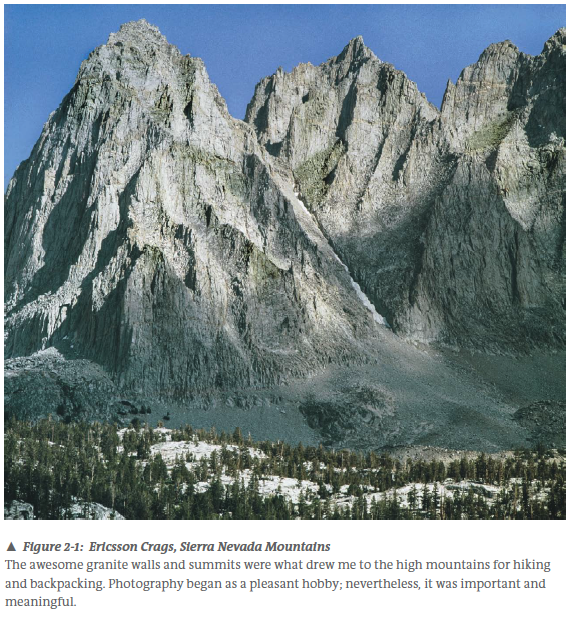

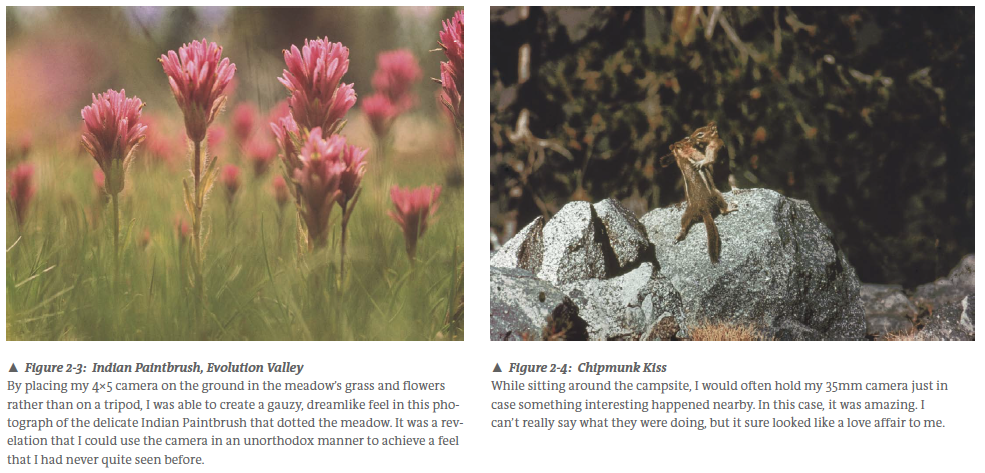

I started photographing in the early 1960s when I was still a college student. My goal was to show the places where I backpacked in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains. I had no thoughts of artistry or of a “personal statement,” or anything of that nature. I had no comprehension of what that term could have meant. I simply wanted to show others the awesome mountain landscape. I was drawn to the power of the Sierra’s huge granite walls topping out at summits above 14,000 feet (figure 2-1), the immense canyons (figure 2-2), the thundering rivers and waterfalls, the serene meadows and lakes (figure 2-3), the giant sequoia and sugar pine forests, and the innumerable little things that you can never expect in advance (figure 2-4). I began recording the scenes on 35mm color slides, and then with larger format cameras.

In the late 1960s, when I was working as a computer programmer, a friend who worked down the hall asked if I’d like to learn how to shoot and develop black-and-white negatives and prints. My initial reaction was, “Hell, no!” I wanted to be in the luminous mountains, not in a dingy darkroom. Somewhere along the way I changed my mind and asked him to show me what it entailed. I found that it really wasn’t terribly difficult, nor was it horribly dingy. I immediately bought a larger camera, somehow not wanting to shoot the small 35mm-negative size, and began photographing the landscape in black and white.

I was further drawn to landscape images when I looked at photographs by others, especially those by Ansel Adams, whose images seemed to be more powerful, more vivid, and more spectacular than any I had ever seen. His work came closest to depicting the landscape—specifically the mountains— as I saw it on my hikes. So in 1970, I took a two-week workshop that Adams conducted in Yosemite. I knew my interest: landscapes, specifically mountain landscapes. I felt I could learn to photograph this subject matter best from the person who I thought was doing it best. Looking back on this now, it’s clear to me that Ansel’s images had that “personal statement” that I failed to comprehend at the time.

Shortly after that workshop, I quit my programming job in the defense industry and went into photography. I had to turn to commercial architectural photography to stay afloat financially, but my personal interest remained with landscapes, which I continued to photograph whenever I could find the time.

Sometime during the mid- to late-1970s my interests began to expand and I started to become interested in more abstract images; not in place of landscapes, but in addition to them (figure 2-5). I immediately ran into a serious roadblock when I was met with a negative response from those who knew my photographic work best, who would look at one of my more abstract pieces and derisively ask, “Is this the same Bruce Barnbaum I used to know?” That response was enough to dissuade me from showing the image or even producing more abstract works—it’s likely I just lacked the self-confidence to follow my own star—but I kept feeling the tug to do something more abstract.

All doubts vanished in August of 1979 when my workshop co-instructors, Ray McSavaney and John Sexton, and I took our workshop students to the home of Brett Weston in Carmel, California. (I started teaching workshops in 1975.) During this visit, Brett showed us an astonishing array of his images, most of which were abstract. I’ll never forget walking out of his home and having one of the students grab me by the shoulder and ask, “What did you think of Brett’s work?” I answered, “Nobody in this group got more out of it than I did.” I knew then and there that his work had a profound influence on me.

Brett Weston had kicked the door of abstraction open for me. I realized that he had freed me up to do what I really wanted to do. What made that transition possible for me was an instant change in my attitude toward abstraction. Up until that time, the skeptical and negative reactions I had received from friends made me feel that presenting an abstract image was irritating to those who couldn’t quickly identify the subject matter. But after seeing Brett’s work, my attitude changed entirely. I now felt as if I were presenting a puzzle—a challenge, if you will—to the viewer. I would then step back to allow the viewer to solve the puzzle, or not. Instead of answering questions with a photograph, I was asking questions. I had suddenly determined that both were equally valid. If some people were irritated with abstraction, so be it; that was their problem, not mine! It was a dramatic change in thinking.

Figure 2-2: Tehipite Valley, North Fork of the Kings River Viewed from Crown Valley, the gaping chasm seemed to go down endlessly, with the polished granite walls rising up in a rhythmic series of spikes. It seems to me that anyone seeing a sight like this would be overwhelmed by its magnificence. My hope was that viewers would gain a feel for the size by comparing the height of the cliffs to the 200-foot-tall trees on the valley floor.

On January 1, 1980, just four and a half months after that extraordinary visit to Brett Weston’s home, I walked into Antelope Canyon, a place so abstract that I never could have imagined its existence. Without hesitation I began to photograph within its narrow confines. Just six months after that, on my way to Norway, where I had been invited to teach a workshop for a handpicked group of professional photographers, I “discovered” the English cathedrals. Prior to leaving home, I would have said that I had no interest in photographing churches, but these structures were so impressive, so monumental, so overwhelming, and so compelling to me that I felt I had no choice but to photograph them.

Within the short time span of six months, my interests expanded from landscapes alone, to abstracts, and then to monumental ancient architecture. Throughout my photographic career I have continued to expand upon existing interests without losing my previous interests. This has worked well for me. Others take a very different approach. Some start with a single interest and remain focused on it throughout their career. Some skip from interest to interest, dropping the previous one as they latch onto a new one. Some start with a variety of interests, and gradually narrow them down to one or two interests that remain with them for a lifetime.

Which is the correct approach? Which is wrong? It turns out they are all correct. None of them is more correct than another. The approach you use has to work for your interests. What has worked well for me may not be good for you, or for another photographer, and vice versa. This is all part of finding your interests and your groove, and it has nothing to do with anyone else’s groove. It’s recognizing that your interests can change, expand, or become more specific. It’s understanding that you are the only one who can determine what you want to do photographically. Only you can determine how you want your photograph to look, what you want to show, what you want to avoid, what you want to emphasize, and what you want to de-emphasize—in other words, what you want your photograph to say. It’s yours, and you’ll find your proper voice and groove in time.

Some photography instructors try to push a student toward a single area of interest. I don’t agree with this approach. We’re multifaceted people. We have more than one interest in life; why can’t we have more than one interest in our photography? As a longtime workshop instructor, I have never tried to push a student into a single area of interest. I may point out the realm in which I feel a student is doing his strongest work, and encourage him to continue to pursue that realm, but I feel that photographers should always look toward other realms as possible wellsprings of inspiration. I see no problem with your pursuit of multiple areas of interest if they turn out to be areas of real passion for you. Why walk away from any of them? Only you can determine your interests, and sometimes one may come as a complete surprise, just as the cathedrals of England did for me. Of course, my discovery of Antelope Canyon and other slit canyons were even more surprising, but that was simply because I never could have imagined places like those existed.